Més que un club. It’s a motto of which FC Barcelona’s fans, directors and marketing department persistently remind us, but not without justification: in European football the club has always been something of an anomaly. As is perhaps to be expected for a club that exists as the world’s most positive and visible source of Catalan pride, Barça have always tended to have their own way of doing things. For a long time these differences extended to the team’s kit. Famously, Barcelona were the last major club in the modern era not to sully their shirt with a commercial sponsor. It seems hard to believe given today’s all too frequent Nike efforts, but not too long ago the blaugrana strip barely changed over the course of a decade. Produced by the Spanish company Meyba, this classic kit was (along with an innate dislike for Real Madrid) one of the few constants at the Camp Nou in the 1980s. The shirt is often listed as dating from 1984-89, but I see no difference in the kits worn either side of that period, which leaves me convinced that it remained unchanged for nine seasons between 1981 and 1990.

For the team it was a turbulent period characterised by strained relationships and only sporadic on-field success, not to mention a slew of big-money signings and big-name managerial casualties. The first of these was the aging Argentine Helenio Herrera, who despite picking up a Copa del Rey with Barça in 1981, could only lead the team to a disappointing fifth-place league finish. Herrera’s replacement was Udo Lattek. The West German maintained a prickly relationship with compatriot Bernd Schuster, but reignited a bond with the Danish forward Allan Simonsen — an old acquaintance from Lattek’s days at Borussia Mönchengladbach. Barcelona reached the final of the 1982 European Cup Winners’ Cup, which just so happened to be hosted that year at the Camp Nou. Though they went behind against Standard Liege, Barça’s home advantage eventually proved the difference, and goals from Simonsen and veteran striker Quini clinched the victory. Though the Catalans finished a close second to Real Sociedad in the league — with Quini securing the Pichichi top scorer trophy for the third season in a row — the Liga title continued to elude them.

Back row: Urruti, Sanchez, Schuster, Alexanko, Julio Alberto, Migueli; Front row: Carrasco, Victor, Alonso, Marcos, Maradona.

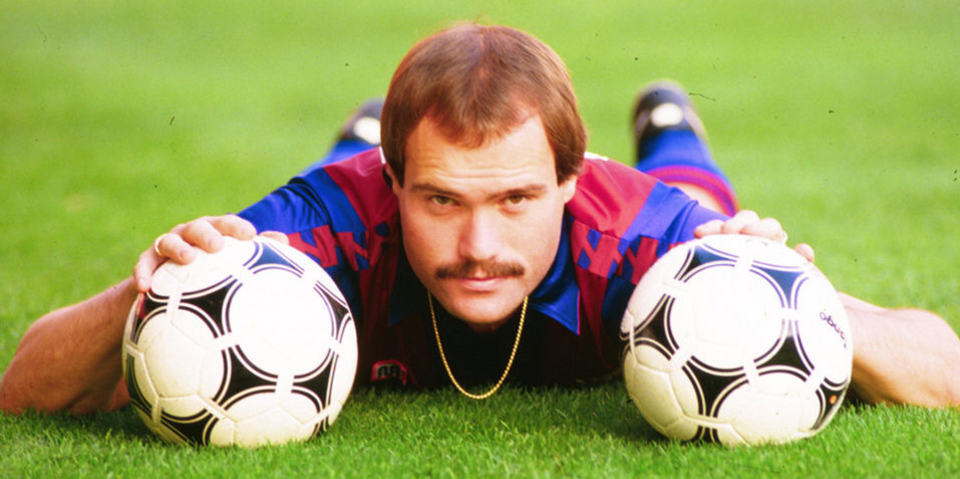

The plan to change that came in the shape of Diego Maradona, who arrived at Barcelona in the summer of 1982. The fee paid to Boca Juniors was a then-record £5 million, but the greatest player in the world seemed worth every penny, at least according to Barcelona’s elected president, Josep Lluís Núñez. Unfortunately the Argentine’s first season in Spain was plagued by a bout of hepatitis, causing him to spend three months on the sidelines. Maradona recovered in time to help Barcelona beat Real Madrid in the final of both cup competitions (the Copa del Rey and the Copa de la Liga), but they could only manage fourth in the league. Lattek departed that summer, and in stepped chain-smoking Argentine César Luis Menotti. Known as “El Flaco”, Menotti had coached Argentina at the last two World Cups; it was hoped that this factor that would help him bring out the best in Maradona. That plan was thrown into jeopardy just four games into the new season, when a reckless tackle by Athletic Bilbao’s Andoni Goikoetxea left the Argentine with a broken ankle. Maradona returned in time to play his part in a shockingly violent Copa del Rey final also against Bilbao, but it was a relatively meagre third place finish in the league that sealed Menotti’s fate.

Impressive results with Queens Park Rangers, and an endorsement from England coach Bobby Robson, helped Terry Venables’ fill the vacant seat on the bench at Barça. With Maradona having left that summer for Napoli, “El Tel” built his team around a strong back four, the commanding Schuster in midfield and a fellow Brit up front: Scottish striker Steve Archibald. It proved a winning combination, as Barça galloped to a tenth title — their first since 1974 — with a ten-point lead over Atlético Madrid. Venables’ was no one-season wonder: his team boasted a nucleus of Spanish internationals, including Victor, Migueli, Julio Alberto, Caldere, Marcos and Carrasco. The side proved strong enough to reach the European Cup Final for only the second time in 1986. Their opponents in Seville were the talented Romanians of Steaua Bucharest. A typically close final ended goalless after extra-time and Barcelona’s lacklustre display was confounded by a remarkable penalty shoot-out, in which they saw all four of their penalties saved by Steaua keeper Helmuth Duckadam.

Carrasco, Migueli, Julio Alberto, Marcos and Caldere.

Keen to recover from that blow, Venables signed two stars of that summer’s World Cup: Spain goalkeeper Andoni Zubizarreta (who would replace the veteran Urruti) and England centre-forward Gary Lineker. Fresh from having won the Golden Boot in Mexico, Lineker was expected to form a deadly partnership alongside Mark Hughes, who had arrived from Manchester United. Unfortunately the Welshman failed to settle in Catalonia, earning himself the pejorative nickname “El Toro” before being swiftly loaned out to Bayern Munich after a single season. Lineker on the other hand quickly made himself at home, and immediately endeared himself to the Barcelona faithful by scoring on his league debut after just two minutes. Later that season “El Matador” bagged a memorable hat-trick against Real Madrid, further cementing his place in Catalan hearts. But despite Lineker’s prolific goalscoring Barça were pipped to the title by Real Madrid for the second year running, this time by just a single point. However it was the ignominy of home and away defeats to Dundee in the UEFA Cup quarter-final later that season that most likely cost Venables his job just a few weeks into the 1987-88 campaign.

The Englishman’s caretaker replacement, Luis Aragonés, remained in charge for the rest of the what proved a tumultuous season on and off the pitch. A government clampdown on tax evasion had seen players asked to have their wages cut in order for the club to repay what they owed the authorities. The row reached its climax in April 1988 when the bulk of the squad convened at the Hotel Heredia calling on Nuñez to resign. In the end the president stayed, with most of his players departing instead. It was clearly time for a fresh start, and the man handed the task of leading Barça into a much-needed new era was Johan Cruyff. With a steadfast conviction in his footballing philosophy, the Dutchman introduced a style of play that had its roots in the Total Football of Ajax. The new manager seemed less than taken with the team he inherited, moulding his new side around several new players: Bakero, Goikoetxea, Amor, Beguiristain and Salinas. Victor, Schuster and Archibald all left the club, while Cruyff preferred the tall Salinas as a target man up front, forcing Lineker out wide on the right wing. From his new position the Englishman inevitably found the net less frequently, but did provide the cross for Barcelona’s first goal in the 1989 European Cup Winners’ Cup Final, in which they beat Sampdoria 2-0.

Bakero, Beguiristain, Salinas, Eusebio; Koeman, Laudrup, Stoichkov.

Lineker rejoined Venables at Tottenham Hotspur later that summer. Carrasco and Quini also left Camp Nou, with Dutch defender Ronald Koeman and the elegant Dane Michael Laudrup arriving. 1989-90 turned out to be the final season for Barcelona’s now familiar kit, in which they had experienced such extreme highs and lows. In 1990 the shirt was modified for the first time since 1981 with the inclusion of a subtle stripe detail woven through the fabric of the shirt. By now Cruyff had begun to assemble what became known as the “Dream Team”, signing the Bulgarian Hristo Stoichkov and plucking homegrown prospects Guardiola and Ferrer from the “B” team. Barcelona finally won the league at Cruyff’s third attempt in 1991, initiating a period of domination that would last for four seasons. Despite losing that year’s Cup Winners’ Cup Final to Manchester United (in which Barça reject Hughes scored twice) the Catalans maintained their momentum in Europe the following season, reaching the European Cup Final at Wembley, where once again they faced Italian champions Sampdoria. A typically close but absorbing contest was settled in extra-time by a bullet-like free-kick from the boot of Koeman. In recognition of the occasion, at the final whistle the team quickly threw on home shirts for the trophy presentation (they’d worn an orange away kit during the match), in which the club’s official captain Alexanko (now playing the role of substitute) was given the honour of hoisting aloft European football’s ultimate prize.

Barcelona’s Wembley victory proved a fitting conclusion to its long association with Meyba. In 1992 the club struck a deal with the Turin-based company Kappa, whose Madrid-white branding along the sleeves of the new shirt caused immediate consternation among fans. Cruyff’s “Dream Team” won four Liga titles in a row, their one misstep a 4-0 capitulation at the hands of Milan in the European Cup Final in 1994. Following Cruyff’s departure, Bobby Robson led a Ronaldo-inspired Barça to a record fourth Cup Winners’ Cup success, before Louis Van Gaal and Frank Rijkaard achieved further success in the Dutch tradition. But it was under Cruyff disciple Guardiola that the Dutchman’s footballing vision reached its extreme peak, and inevitable conclusion. Between 2009 and 2012 Barcelona became an almost unstoppable force at home and in Europe, developing a style of possession football that became known by the onomatopaeic term tiki-taka. Of course, this period of consistency was contrasted by annual — and at times radical — changes to the club’s once-iconic strip. A complete reversal from the 1980s, when Barça changed everything but their kit.