Success was so swift and so absolute for Silvio Berlusconi’s Milan, that it’s easy to forget when he had taken over the presidency the once prestigious club found itself ridden in debt, having spent two seasons in Serie B in the early 1980s. Though the team already boasted some talented local youngsters including Baresi, Maldini, Donadoni and Evani, their foreign stars were aging. Milan lacked that special player — a Maradona or a Platini — necessary to make the extra leap to domestic and European glory. In the summer of 1987 Berlusconi’s finances (funded at the time by his growing media empire) helped secure the talents of young Dutch stars Ruud Gullit and Marco Van Basten. That season Milan pipped Champions Napoli to the Serie A title, their first scudetto in nine years. Later that summer Gullit and Van Basten proved instrumental in Holland’s first major trophy, the European Championship, and after the tournament their international teammate, Frank Rijkaard, joined them at Milan.

Berlusconi’s influence was not only economical. He insisted his side produce attractive, attacking football, and his power wielded an unprecedented control over transfers, team selection and technical aspects of the side’s preparation. In Arrigo Sacchi he found the ideal coach, an eccentric but brilliant man, who, despite fielding an imperviously strong back four, represented the antithesis of catenaccio. By the end of the decade Milan were once again the dominant force in Europe, winning back-to-back European Cups in 1989 and 1990, a trophy which had eluded them for twenty years. They topped those victories off on both occasions with successive triumphs in the Intercontinental Cup in Tokyo.

Through regular visits to Italy and my burgeoning fixation with calcio I’d become fascinated by Sacchi’s Milan side, and in 1991 I bought the famous maglia rossonera from a store in the northern Tuscan town of Aulla. Given the quality of its domestic league football in Italy was remarkably uncommercialised in those days. All the shirts in the shop were folded in their manufacturers’ plastic wrappers and stacked up to the ceiling; after inquiring about the Milan kit a lady climbed to the top of a ladder to retrieve my size. The shirt was only available with long-sleeves, which seemed impractical to me at the time (it was July) but wholly appropriate once I recalled images of San Siro shrouded in a thick fog, the rossoneri carving out victories from its frosty turf.

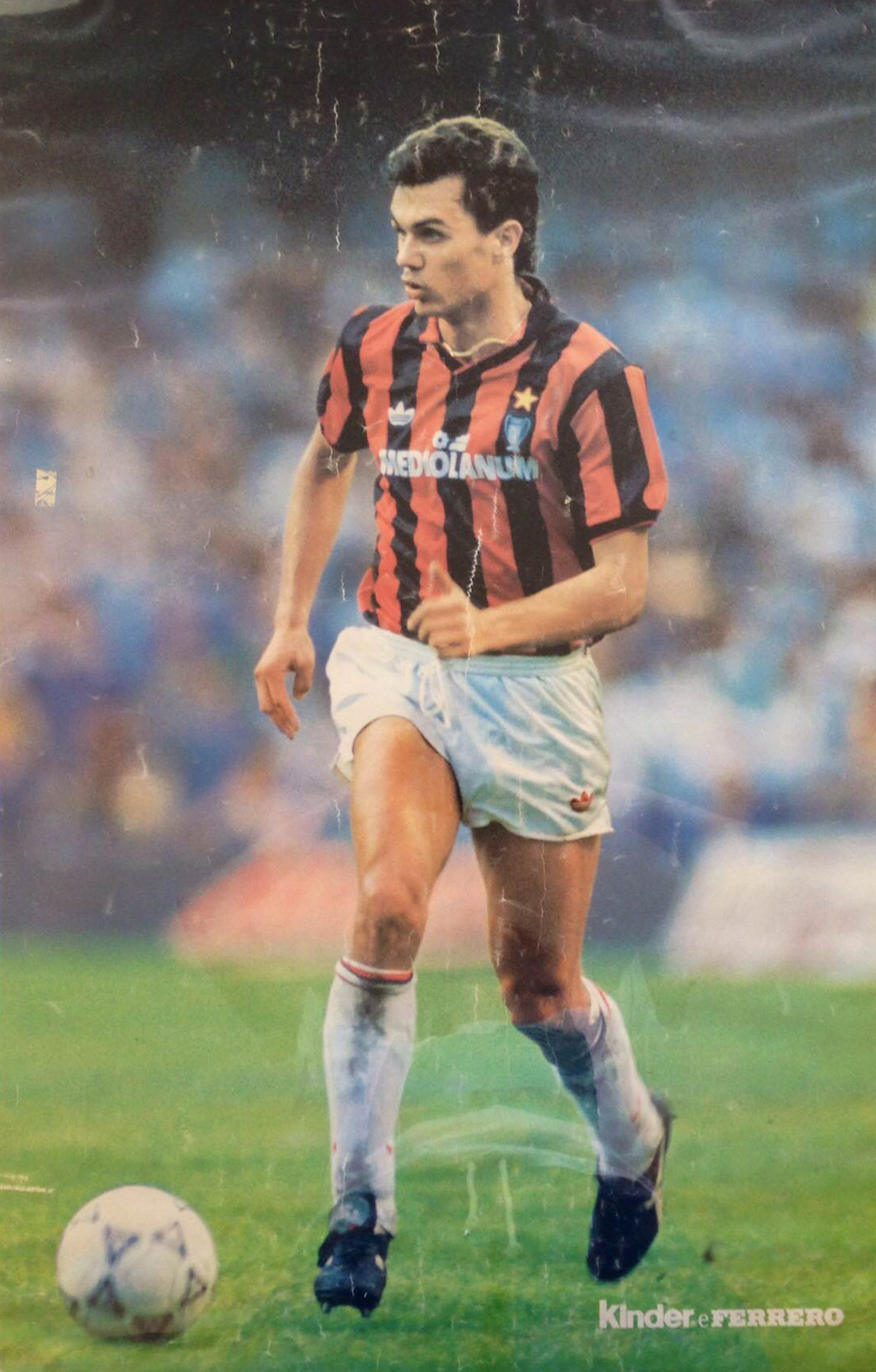

Milan had changed kit manufacturer in 1990, switching from Kappa to adidas, but the shirt had remained essentially unchanged for the last four years. The sponsor was still Mediolanum, Berlusconi’s own insurance company, named for the Latin word for Milan (the city). Above it on the right was the gold star which is earned after ten scudetto wins, beneath which sat an embroidered European Cup celebrating the fact that Milan were the current holders of that trophy (a nice initiative which never caught on). In the 1990-91 season Milan finished second in Serie A, a full five points behind scudetto winners Sampdoria, to whom they lost twice. A defeat to lowly Bari in the penultimate match of the season effectively ended their title hopes.

Milan’s good domestic showing was marred by a disastrous European Cup campaign. The rossoneri were aiming for a record-equalling third straight triumph in the competition, and came up against a talented Olympique Marseille team in the quarter-final. The first leg at San Siro ended 1-1; in the return match Chris Waddle had given the French champions the lead on 75 minutes when deep into injury time the floodlights at the Stade Velodrome failed. When power was restored after several minutes Milan refused to return to the pitch – a gesture which most interpreted as a desperate attempt to seize the opportunity for a rematch. Either way the tactic backfired: UEFA awarded a 3-0 result to Marseille, while Milan were banned from all European competition for the 1991-92 season.

His time at Milan having clearly run its course, Arrigo Sacchi left the rossoneri that summer to take over the Italian national team. Under his replacement, Fabio Capello, Milan galloped to a record-breaking Serie A season, becoming the first side to win lo scudetto without defeat. Van Basten finished the season as top scorer with 25 goals. The shirt remained unchanged from the previous season, although since Milan were no longer holders of the European Cup, its presence on the shirt was replaced by the Intercontinental Cup; when Red Star Belgrade took this title away from them in December 1991 they reverted to a traditional Milan logo (incidentally the first appearance of the club crest on the rossoneri jersey).

Milan collected three successive Serie A titles with Capello at the helm, and with success on the pitch changes to the kit remained subtle over the next few seasons. In 1992 a new sponsor arrived in the form of local dessert company Motta, and the following year a new kit deal was launched with the Italian sportswear manufacturer Lotto. Milan re-established their relationship with adidas in 1998, by which time they’d begun a long-term sponsorship by the German car giant Opel.

As Berlusconi ventured into politics his desire to create a European supersquad had resulted in the arrival of some big names — Savicevic, Boban, Papin, Raducioiu, Lentini — all of whom now competed for positions in Milan’s line-up. As Capello struggled with the challenge of keeping his bloated roster of big names happy, the Dutch trio’s dominance became undermined and was effectively broken up. The last time the three played together was the 1993 European Cup final in Munich, a 1-0 defeat by old rivals Marseille. That summer Rijkaard returned to Ajax and Gullit unexpectedly left for Sampdoria. Van Basten stayed at Milan, unaware he’d already played the last game of his career. He remained on the sidelines throughout the 1993-94 season, missing out on the team’s European Cup triumph and that summer’s World Cup, before finally announcing his official retirement in 1995 at the age of 30.

The same summer I bought my Milan shirt I also obtained a giant poster of a young Paolo Maldini wearing the same kit. It was free from the local supermarket in exchange for the purchase of several packets of apricot jam-filled Kinder brioche (my brother got Baggio). Something about the lighting always made me believe the photo was taken at the San Paolo in Naples (the ball is correct, Paolino wore short-sleeves in that fixture, and there’s clearly an ad for Mars in the background). Either way the poster hung pinned on my bedroom wall for over a decade, and now hangs framed in my apartment in New York, just feet from where I sit as I write this. A few years ago adidas relaunched the 1990-91 shirt as a limited edition replica, presumably for fans who now regretted not getting their hands on it the first time. Yet somehow the remake wasn’t quite the same. The sponsor was too large and the slightly bulbous adidas logo had been corrected. The material was too glossy, too well-made. It was as if the memories of both the shirt’s manufacturer and its consumer had been warped by the team’s own legend. Milan weren’t perfect, and nor was their shirt. But both came mighty close.