Category: 1990s

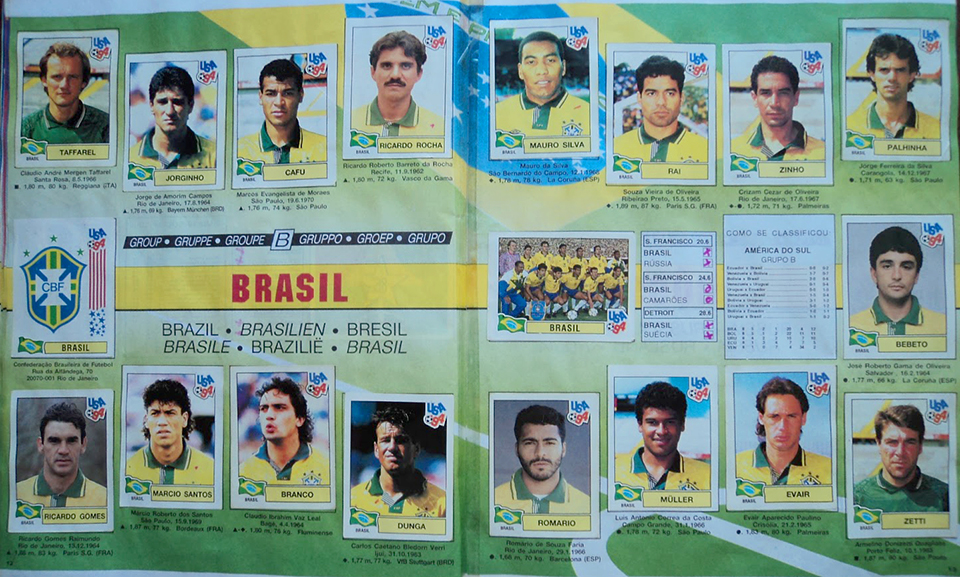

Brazil 1991-93

When the Confederação Brasileira de Futebol announced a new kit deal with English company Umbro in 1991 for many fans it was the end of an era. Brazil’s kits in the last three World Cups had been manufactured by the South American brand Topper, barely altering in that period, so it was hard to imagine the Seleção wearing anything else. (Brazil had worn Umbro kits at the 1962 and 1970 World Cups, but without access to the team’s changing rooms few fans could have been aware of this fact.)

After finishing runners-up at that summer’s Copa America in Chile, Brazil introduced its new Umbro kit in a 3-1 win over Yugoslavia in October 1991. But these were the days before internet or even cable TV, and so my first close glimpse of the new shirt came in May 1992 when Brazil faced England at Wembley, a game I watched on the BBC. The match ended in a 1-1 draw, with goals from Bebeto and Platt, but was best remembered for Gary Lineker’s squandered penalty, an uncharacteristic miss which denied him the honour of equalling Bobby Charlton’s record tally of 49 goals for his country.

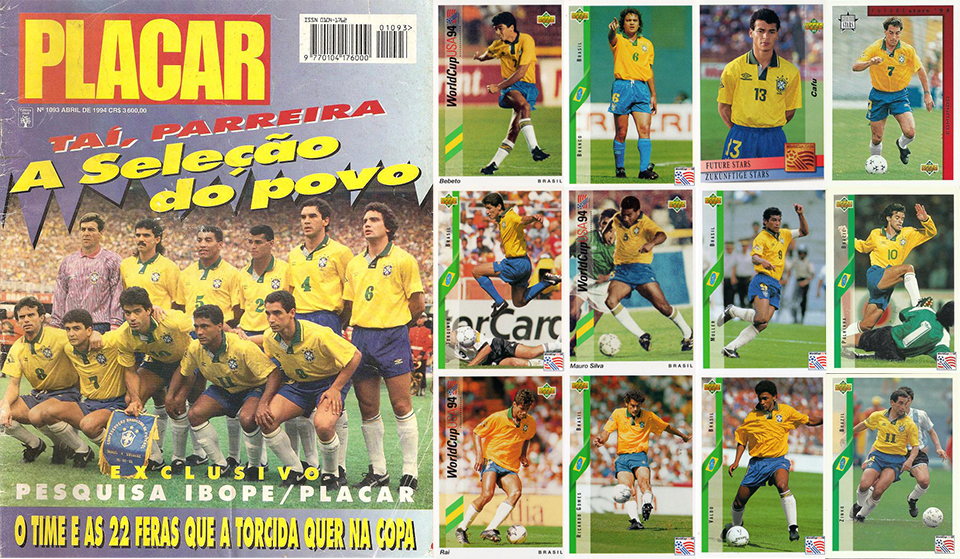

My parents bought me the new Brazil shirt that Christmas. As was typical of the Umbro kits of the time, it featured an abstract “CBF” pattern on the sleeve that was echoed throughout the fabric. The shirt was essentially a yellow version of the Tottenham kit of the same period. I later bought myself a pair of blue Umbro shorts to further enhance the look when kicking a ball about at the park or in the garden. Two minor changes occurred to the kit between ’92 and ’93. The pattern at the top of the socks reverted to a traditional green and yellow stripe, while the classic English-style Umbro player numbers that had been used initially were replaced by an outsized poster typeface that was decidedly more South American (both Mexico and Argentine club Newell’s Old Boys sported similar numbers at the time). Brazil and England drew drew 1-1 again the following summer, this time at the RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C. The occasion was the US Cup, essentially a preparatory warm-up for the organizers of USA ’94. Brazil beat the hosts 2-0 at the Yale Bowl and drew 3-3 with world champions Germany, against whom veteran striker Careca scored his last international goal.

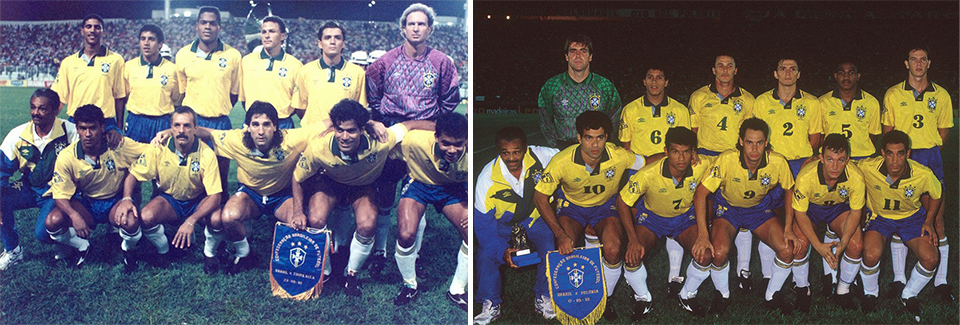

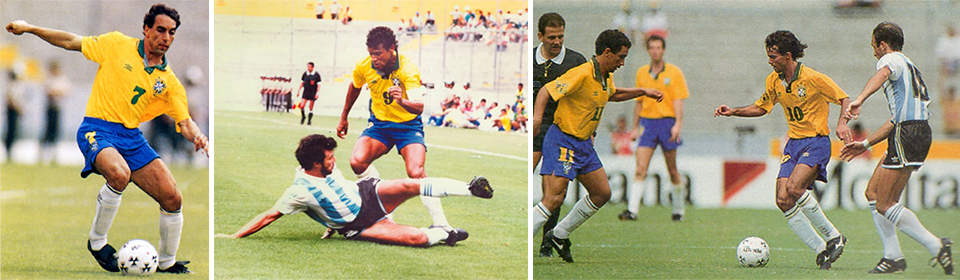

Just eight days later Brazil were back in action opening their Copa América account in Ecuador. Carlos Alberto Parreira’s squad was made up almost exclusively of home-based players. This allowed young full-backs Cafú and Roberto Carlos a chance to impress, but it also meant the absence of experienced key men such as Jorginho, Branco, Bebeto and Raí, as well as PSV forward Romário. The striker had been not been called up to the national team since December, when he’d not hidden his frustration at travelling from Eindhoven to Porto Alegre for a friendly match only to be kept on the bench. In such circumstances, the team struggled in the first round. A goalless draw with Peru was followed by a 3-2 defeat to Chile. It was left to unproven talents Edmundo and Palhinha to engineer a 3-0 victory over Paraguay, a result which ensured qualification and briefly restored some optimism. In the quarter finals Brazil met their old foes Argentina, whose goalkeeper Sergio Goycoechea yet again proved decisive, saving Boiadeiro’s penalty in an epic shoot-out.

Later in 1993 I also obtained a rare training top as used by Brazil at that summer’s Copa América. Made of heavyweight cotton and featuring some lovely embroidery, it was the kind of thing that teams don’t seem to wear to train in anymore, and as a result now looks quite retro. The design certainly screams mid-nineties, but it made me the envy of several classmates during the 1993-94 school year. I recently rediscovered this special garment at my parents’ house back in England, where it has been perfectly preserved for the past twenty years.

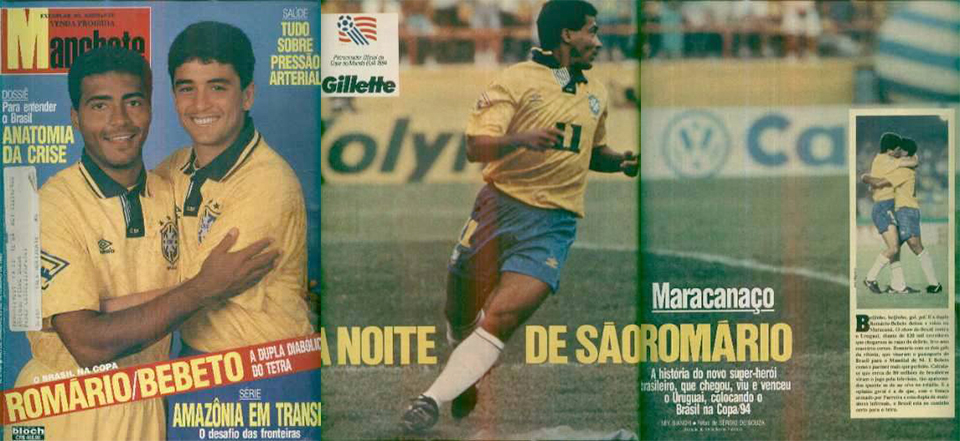

Brazil’s busy summer continued as a tightly scheduled qualification for the 1994 World Cup commenced. The team found it tough to shake off the Copa América disappointment, drawing 0-0 with Ecuador and losing 2-0 to Bolivia. A five-goal thrashing of Venezuela steered the Seleção back on course, and they ended their turbulent campaign with a spectacular run of results. In the space of two weeks they beat Ecuador, Bolivia and Venezuela, scoring twelve goals without reply. In their final qualification match Brazil needed a win against Uruguay at the Maracanã in order to finish top of the group and secure their ticket the USA. Under increasing pressure from fans and journalists, Parreira finally succumbed and recalled Romário, who had not featured in any of the qualifiers thus far. Back in this hometown stadium the Barcelona forward scored both goals in a 2-0 victory. When asked about his decision afterwards Parreira stated, “God sent Romário to the Maracanã.” Meanwhile, Copa América champions Argentina had faltered, conceding five goals at home to Colombia in Buenos Aires (a record home defeat) and eventually requiring an own goal in a last-gasp play-off with Australia to book their berth in the pot for the World Cup draw.

Umbro unveiled a new Brazil shirt in time for the tournament in the United States, where as usual Brazil were counted among the favorites, though Parreira was quick to play down their chances. They couldn’t even count on the backing of Pele, who maintained that dark horses Colombia would lift the trophy. As it happened both were happy to be proven wrong. In the glistening sunshine of Pasadena Brazil became the first nation to win a fourth World Cup, a victory that put an end to a twenty-four year spell in the relative wilderness. Though blessed with talent and a decisive cutting edge up front in the pairing of Bebeto and Romário, Parreira’s team was perhaps less flamboyant than previous Brazil sides. Some described them as excessively “European”, a harsh criticism perhaps given that the nucleus of the team had been based in Europe’s top leagues for years. Romário emerged as one of the stars of the competition, but for the elegant number ten Raí it was a less positive World Cup. The Paris Saint-Germain midfielder had gone into the tournament as first-choice playmaker and captain, only to lose his place to Mazinho following the group stage. In the knock-out phase he was only used as a substitute, and missed out on the final altogether. Consequently, Dunga, who had taken over the armband, got to lift the trophy at the Rose Bowl. It seemed unfair that Raí was not offered the chance to share this honour, and his international career subsequently fizzled out.

Brazil’s period with Umbro ended in the summer of 1997, when CBF launched its first kit manufactured by Nike, at the time still a marginal player in terms of soccer apparel. Every Brazil shirt for the last fifteen years has been emblazoned with the iconic swoosh device, instantly familiar to fans everywhere from Bangladesh to Belo Horizonte. The days of Topper and Umbro were long gone, and a global homogenization of football kits had begun.

Brazil 1998

Coming soon…

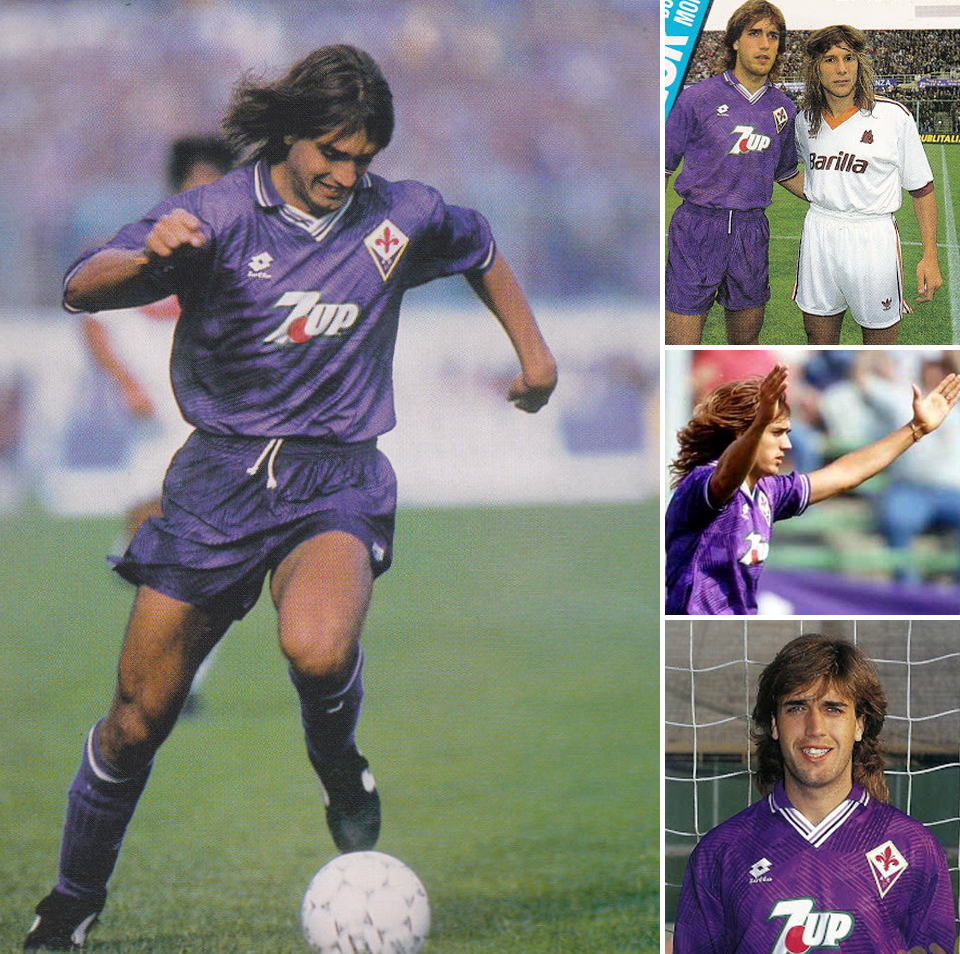

Fiorentina 1992-93

In the summer of 1990 Fiorentina entered a new era. Having just suffered their worst Serie A finish in over a decade under Italian World Cup-winner Francesco Graziani, it was then revealed that Roberto Baggio would be sold to Juventus for a world record 25 billion lire. The transfer of la Viola‘s star player to its bitterest rivals provoked violent protests on the streets of Florence, coming just two days after Juventus had beaten Fiorentina in the UEFA Cup Final. Even Fiorentina’s headquarters in Piazza Savonarola came under attack, duly prompting the club’s owners, the Pontello family, to hand over operations to film producer Mario Cecchi Gori.

The team failed to improve in its first season without Baggio, for which Cecchi Gori immediately attempted to make amends. In what was undoubtedly the most significant business deal of his presidency, Cecchi Gori signed young Argentine forward Gabriel Batistuta. The dashing striker had just helped lead his country to victory in the Copa America in Chile, after having scored thirteen goals for Boca Juniors the previous season. He continued this impressive scoring rate in Italy, finding the net thirteen times in his debut season in Serie A. But despite Batistuta’s goals Fiorentina still failed to challenge the league leaders, finishing a mediocre twelfth for a third successive campaign. In the summer of 1992 it was hoped that the arrival of blond German midfielder Stefan Effenberg and elegant Danish winger Brian Laudrup — the latter a freshly-crowned European Champion — would make the difference.

Luigi Radice, who’d coached Fiorentina to sixth place in 1974, was again at the helm, having replaced Brazilian Sebastiano Lazaroni early in the 1991-92 season. His team started slowly, drawing three of its first four games. Although goals were easy to come by — Fiorentina put seven past a hapless Ancona in week three — keeping them out at the other end proved more difficult, and after five games they’d already conceded thirteen goals, seven of which came at home against a ruthless Milan side. The team from Florence responded well to this setback but impressive victories against Sampdoria, Roma and even Juventus were countered by defeats to Cagliari, Napoli and Atalanta. This loss at home to the side from Bergamo proved Radice’s last in charge, and he was replaced by another former Viola coach, Aldo Agroppi.

At the time of Radice’s sacking Fiorentina were in a respectable sixth in Serie A. By the time Agroppi was let go following a 3-0 hammering at Juventus, the team had plunged towards the relegation zone, having racked up just two victories (against Pescara and Cagliari) under his reign. With just five games remaining former striker Luciano Chiarugi was handed the unenviable task of rescuing Fiorentina’s season. But the damage had already been done, and three more draws and a defeat against Atalanta left the team in the drop zone. Yet la Viola were still in with a chance of avoiding disaster as they went into their final game, in which they played host to Foggia. By half-time the home side had galloped into a four-goal lead and looked to have made themselves safe, despite fellow strugglers Brescia winning at Sampdoria. But with ten minutes of the season remaining, Udinese midfielder Stefano Desideri’s spectacular equaliser against Roma lifted his side above Fiorentina, whose fate was suddenly taken out of their own hands. There was still time for more late goals in Florence (the game finished 6-2) but the final minutes were played in a funereal atmosphere. Despite finishing with the same points total as Brescia and Udinese, and just six points behind seventh-placed Sampdoria, the unthinkable had become a reality: Fiorentina were relegated to Serie B after fifty-four consecutive years in the top flight.

The man asked to lead the club back to Serie A was Claudio Ranieri. The former Napoli coach decided that Serie B was the perfect place to thrust a handful of promising youth talents — including goalkeeper Francesco Toldo and forwards Anselmo Robbiati and Francesco Flachi — into the first team. These additions joined an already strong squad. Although Laudrup was quickly offloaded to Italian champions Milan, the rest of Fiorentina’s players seemed content to help the side out of the mess in which it now found itself. Batistuta and Effenberg were commended for showing such loyalty at the risk of losing their places in their respective national sides, and in a World Cup year no less. The Argentine, now known by the Florentine faithful as “Batigol”, again found the net sixteen times during the 1993-94 campaign, atop a scoring chart that also included future Serie A legends Oliver Bierhoff (Ascoli), Enrico Chiesa (Modena), Filippo Inzaghi (Verona) and Christian Vieri (Ravenna).

Fiorentina’s kit from 1991 to 1993 was produced by Lotto, in a design that matched the template worn by the Dutch national team in the same period. In 1991 the club ditched the stylised “F” logo reverted to a traditional kite-shape crest. In 1992 the shirt saw small modifications to the collar and sponsor, which changed from Giocheria (an Italian toy company) to the internationally-recognised soft drink 7-Up. It was Fiorentina’s away shirt that season that drew most attention for its unfortunate swastika-like motif hidden within the purple pattern across the sleeves and shoulders. The shirt was worn in four away games before the now infamous design flaw was pointed out, after which la Viola reverted to a plain white strip. I bought the 1992-93 home shirt from Casa dello Sport, a veritable mecca for football shirt enthusiasts located in Via de’ Tosinghi in the heart of Florence’s centro storico (I later picked up the shorts and socks to match). Fiorentina kept the same look during their season spent in Serie B, although the kit was now manufactured by the German company Uhlsport. When the side returned to Serie A in 1994 a new sponsorship deal was struck with Tuscan ice cream company Sammontana.

My first ever visit to the Stadio Artemio Franchi occurred while la Viola‘s were languishing in Serie B, in a league fixture against Modena in April 1994. The match was played under a torrential downpour; ironically Fiorentina’s free-flowing goalscoring form had completely dried up, and the game finished goalless. Nevertheless, in the end Fiorentina bounced back to Serie A comfortably, eventually finishing on top of Serie B, five points ahead of second-placed Bari. Sadly Mario Cecchi Gori didn’t live to see the side gain promotion, having died in late 1993, at which point the club was taken over by his son, Vittorio. With Effenberg returning to Borussia Mönchengladbach following promotion, the club now needed to bolster their squad if they were to make an impact in Serie A. Brazilian Marcio Santos arrived from Bordeaux, having just won the World Cup in the United States. But the central defender’s time in Florence was brief, and he moved on to Ajax after a single season in Italy. Fiorentina’s other big signing fared a little better. Manuel Rui Costa had broken into Benfica’s first team as a teenager and was already an established name in the Portuguese national side. To the delight of the Viola fans, the young Portuguese playmaker developed an immediate understanding with Batistuta, who found the net in the first eleven games of the season, beating a record held since the 1950s by Ezio Pascutti of Bologna. With his twenty-six strikes that season, the Argentine also equalled Kurt Hamrin’s record of most goals scored by a Fiorentina player in a single league campaign. But despite “Batigol” more than living up to his nickname, and Rui Costa’s emergence as one of Serie A’s finest number tens scoring, Fiorentina’s form began to slip after the new year, and they eventually finished a disappointing tenth, failing to qualify even for the UEFA Cup.

Yet the disappointment was tempered with the fact that Fiorentina had finally turned a corner. The nightmare of relegation was behind them, and in Batistuta they’d found a new hero to take over the mantle of Baggio. Over the next few seasons Fiorentina continued to grow stronger, with Batistuta, Rui Costa and Toldo remaining key men in a side that ultimately began to challenge for top honours at home and in Europe. But just when it seemed the club was enjoying its best spell in years, so the fun came to an abrupt halt. The 1990s had been certainly been a rollercoaster of a decade for Fiorentina, but it was nothing compared to what was to come, as la Viola entered the most turbulent and dramatic period in its history.

Fluminense 1992-93

Coming soon…

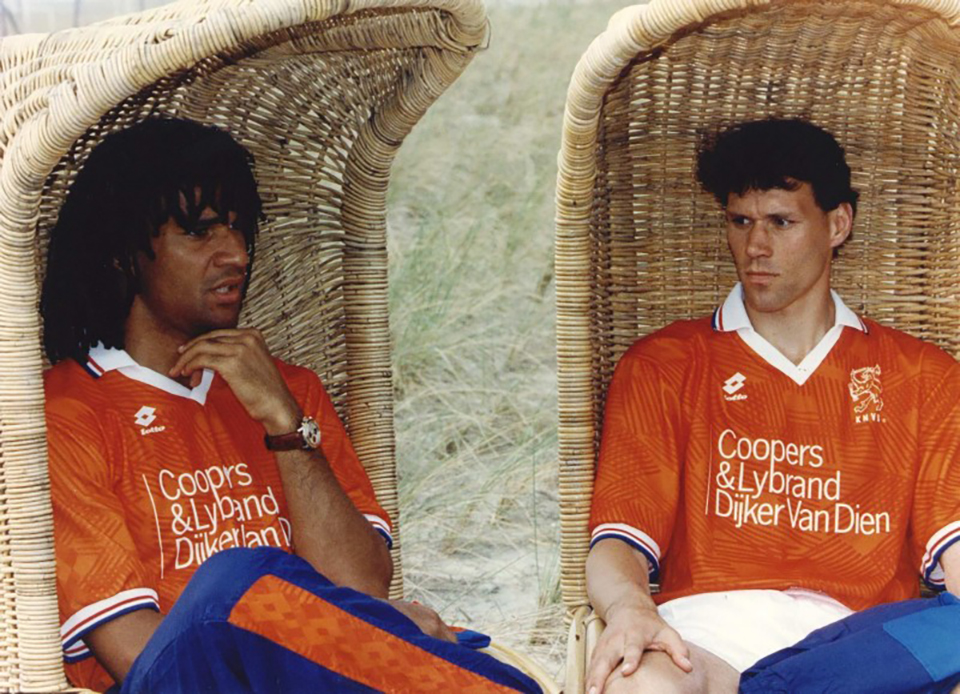

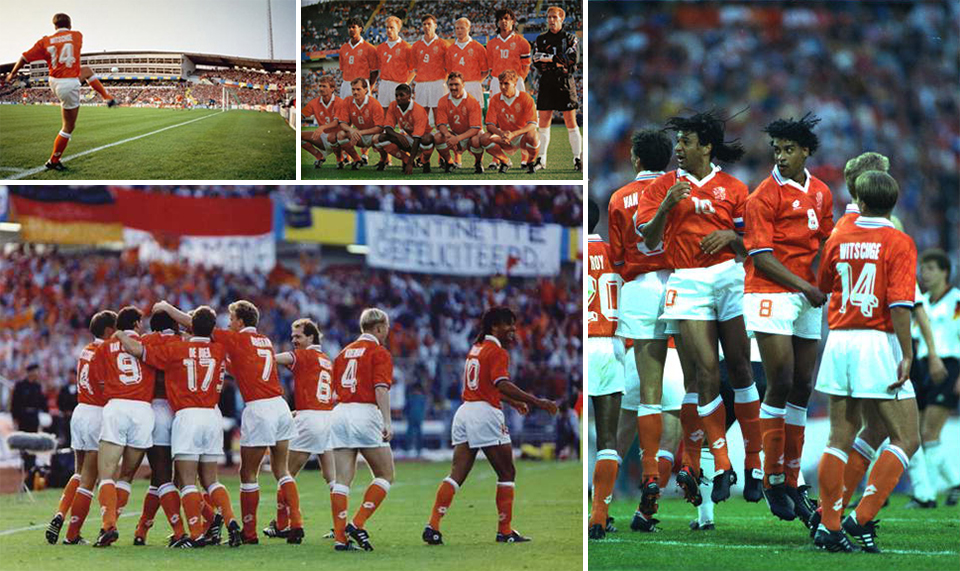

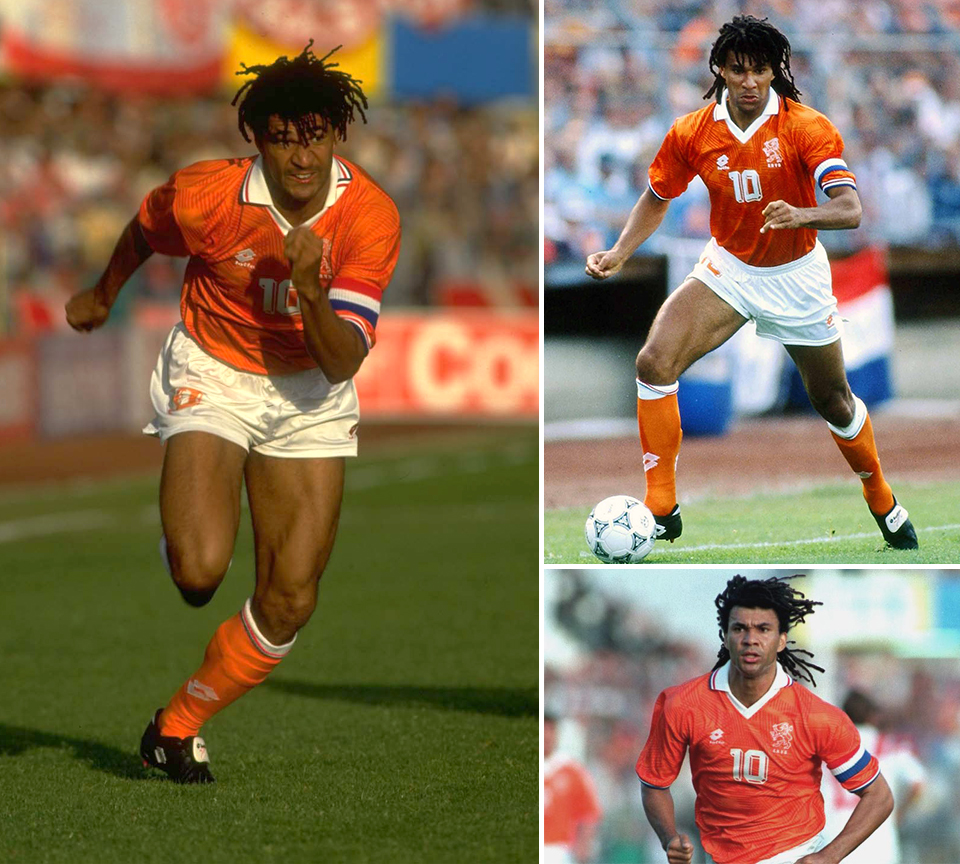

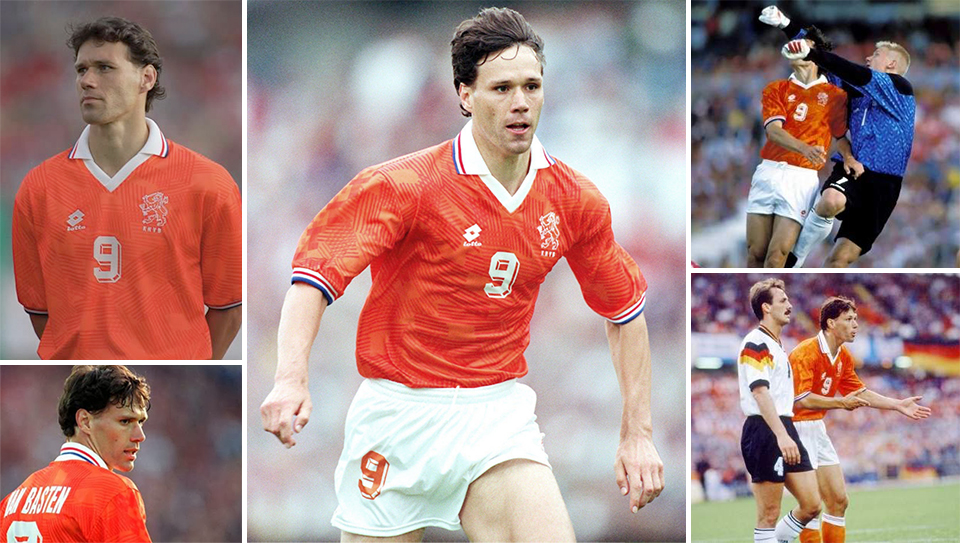

Holland 1991-93

When Holland won the 1988 European Championship it not only secured their first major international trophy but also ended a long period in the wilderness. The Dutch had been unlucky to lose consecutive World Cup Finals in the 1970s, but had then failed to qualify for neither the 1982 or 1986 competitions, nor the European Championships in 1984. So impressive was the victory in West Germany that much was expected of the Dutch side that arrived at the 1990 World Cup. In the interim the trio of Ruud Gullit, Marco Van Basten and Frank Rijkaard had helped make Milan the continent’s most feared club side, winning back-to-back European Cups. Unfortunately a series of managerial switches between qualification and the start of the tournament had left the squad tense, unstable and prone to internal bickering. Meanwhile, Holland’s star players failed to show their true worth. Gullit was still recovering from injury, Van Basten failed to find the net, and Rijkaard compounded a miserable tournament by getting sent off in the defeat against West Germany for spitting on Rudi Völler.

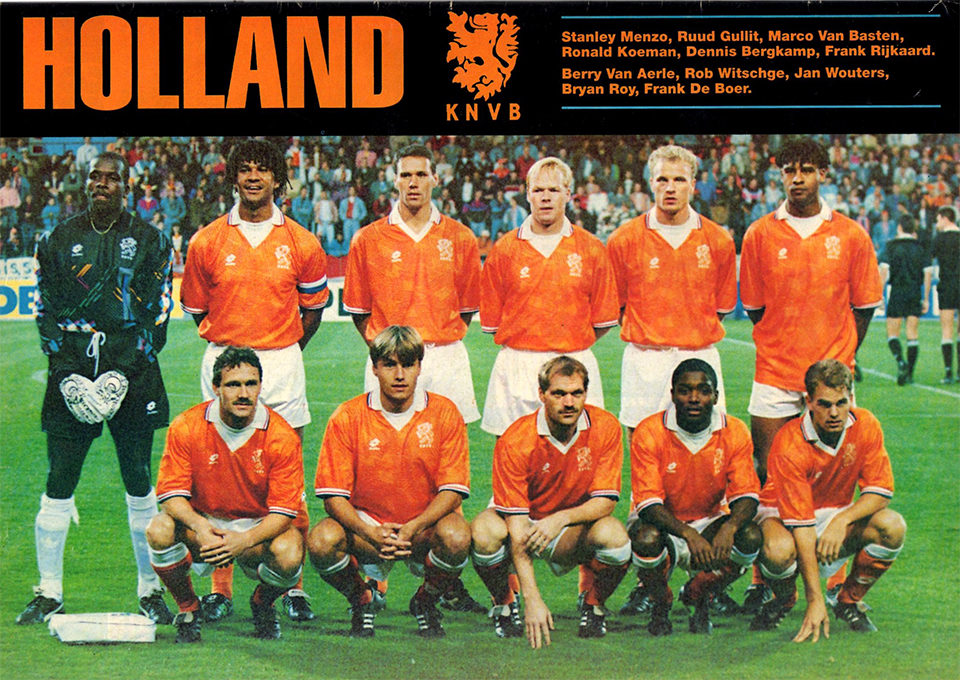

The man who had led Holland to their ’88 triumph, Rinus Michels, returned to the Dutch bench in time for the 1992 European Championships in Sweden. Michels had spent his entire playing career at Ajax, and as a coach became the truest practitioner of the Amsterdam club’s concept of “Total Football”. The philosophy’s greatest disciple on the pitch, Johan Cruyff, played under Michels at both Ajax and Barcelona, not to mention the national team that dazzled at the 1974 World Cup. By the early nineties the free-flowing nature of those sides had been reigned in, but elements of the style remained. The most noticeable difference to the Dutch side was its kit. The KNVB’s long-standing relationship with adidas had ended at the close of 1990; in a qualifier against Malta in March 1991 Holland debuted a new kit produced by Italian company Lotto. The shirt’s most marked characteristic was a unique pen-effect pattern woven into the fabric that echoed the brand’s logo. The white collar and cuffs featured a red-white-and-blue tri-colour trim in the style of the now familiar Italy shirt. Even the 3D numbers were the same as those worn by the Azzurri. It’s also worth noting that this was the first major senior tournament to incorporate front numbers and names on the back of shirts. Although only one member each of the three Dutch sets of soccer-playing brothers — Koeman, Witschge and De Boer — made the Holland squad, the initiative did prove handy in helping to distinguish between mustachioed defenders Van Tiggelen and Van Aerle (not to mention the various Anderssons and Nielsens in the Sweden team).

Michels selected twelve players from his successful ’88 squad, the same twelve that had also gone to Italia ’90. This experienced group provided the backbone of the Holland side that attempted to defend their title. Two young additions to the team were elegant forward Dennis Bergkamp and winger Bryan Roy, both from Ajax. It was Bergkamp who made his mark early on the tournament, scoring the only goal of Holland’s first match against Scotland. A goalless draw against the CIS (a provisional post-Soviet national team following the break-up of the USSR) was enough to see the Dutch through to the semi-finals, but there remained the small matter of a grudge match against Germany. A late Van Basten goal had beaten the West Germans in the ’88 semi-final in Stuttgart; two years later West Germany had knocked Holland out of the World Cup in Milan. Now they met for the third tournament running in Gothenburg, where the Dutch sailed into an early two-goal lead through a Rijkaard header and a low drive by Feyenoord’s Rob Witschge. Jürgen Klinsmann pulled a goal back after the interval but Bergkamp scored his second headed goal of the tournament to seal a memorable 3-1 win.

In their semi-final Holland faced surprise package (and eventual tournament winners) Denmark, who were only competing in Sweden due to war-torn Yugoslavia’s late disqualification. Bergkamp and Rijkaard were again on hand to respond to Henrik Larsen’s double strike, forcing the game into extra-time and towards the inevitable shoot-out. Four years earlier Dutch goalkeeper Hans Van Breukelen had saved from Benfica’s final penalty to win the European Cup for PSV Eindhoven. But this time it was his opposite number Peter Schmeichel who stopped the decisive kick, from the right foot of Van Basten no less. It was a sad end to another disappointing tournament for the striker. A textbook volley that crashed against the German crossbar proved to be the only glimpse of the devastating form he’d shown in 1988.

I didn’t wear my Holland shirt at Wembley the night the Dutch visited England for a World Cup qualifier. Though I was delighted to see two of my idols, Gullit and Rijkaard, in the flesh, I was still not over the disappointment of discovering that Van Basten had been ruled out of the game due to an ankle injury — one from which he never recovered. The striker did return In May to play a couple more games for Milan, including the European Cup Final defeat to Marseille which proved to be his final professional appearance. After conceding two early goals — the first an expertly taken free-kick by John Barnes after a few seconds — Bergkamp got one back at the other end, deftly lobbing Chris Woods in the England goal. Late in the second half pacy central defender Des Walker for once struggled to keep up with his opponent, and was compelled to bring down 20-year-old Ajax winger Marc Overmars inside the box. Subsitute Peter Van Vossen converted the kick to earn the Dutch a point.

Surprisingly, Norway were proving the strongest side in the group. Having lost in Oslo earlier in the summer, England could now not afford to lose their return match against the Dutch in Rotterdam the following October. But lose they did, prompting Graham Taylor’s infamous “Do I not like that” remark. Holland sealed the points with two goals in quick succession, the first a cleverly chipped free-kick from Koeman. English fans argued that the defender should have already received a red card for a professional foul on Platt. Bergkamp headed a second a few minutes later, and England’s hopes of qualifying for USA ’94 were effectively over.

At the 1994 World Cup the Dutch wore an almost identical shirt, the only changes being the shirt’s background pattern (that now featured a repeated KNVB crest) and the replacement of the 3D numbers with a more conventional flat white font. The team were already without Van Basten, who hadn’t played since May ’93, and on the eve of the tournament lost Gullit, who after a long-running feud with coach Dick Advocaat stormed out of a training session. Neither player would ever play for his country again. So Rijkaard was one of only four players from the ’88 squad still involved with the national team. In the stifling heat of Orlando the Dutch stuttered through their group: a defeat against neighbours Belgium was sandwiched between two narrow victories over Saudi Arabia and Morocco. Yet somehow they finished on top having scored more goals against their direct rivals. The speed of Bergkamp and Overmars made easy work of an exhausted Ireland in the second round, but in the quarter-final in Dallas the Dutch succumbed 3-2 to eventual winners Brazil.

Holland’s second goal in that defeat was scored by Aron Winter. With Rijkaard, Koeman and Wouters having all retired from international football after the World Cup, the Lazio midfielder remained the only survivor from 1988 included in Guus Hiddink’s squad for the 1996 European Championships. For the tournament in England Holland’s Lotto shirt underwent further modifications. A button-up collar was added, while the tricolour trim became a broken stripe resembling something akin to morse code. The shirt fabric incorporated the image of Dutch players celebrating a goal at USA ’94. On the pitch Holland struggled again, drawing 0-0 with Scotland and beating Switzerland. Only a late Patrick Kluivert consolation goal in a 4-1 defeat against the hosts saw them through the group on goals scored. In the quarter-finals they lost to France on penalties after another goalless draw.

Euro ’96 was the last tournament in which the Dutch wore Lotto. For the 1998 World Cup in France they had struck a deal with Nike, whose uniforms they have worn ever since. Winter remained a part of the international fold for that tournament and was even selected for the one that followed — Euro 2000, which Holland co-hosted — by old teammate Frank Rijkaard, who was now in charge. Several of Holland’s Nike shirts have made great use of black as a secondary colour (which was totally absent from all the Lotto kits), presumably in an attempt to reference past glories. But none have inspired the team to a second international success, just as I have yet to be compelled to add any of them to my collection. Personally I thought the 1988 kit was hideous at the time, an opinion which has not changed despite its recent new-found status of cult favourite (a case of a lousy shirt being elevated alongside a winning team). I much preferred the clean kit worn at Italia ’90 and the Italian style Lotto strip sported at Sweden ’92. That was also the last time Gullit, Rijkaard and Van Basten played together, and the last time I genuinely enjoyed watching the Dutch — none of which can be a total coincidence.

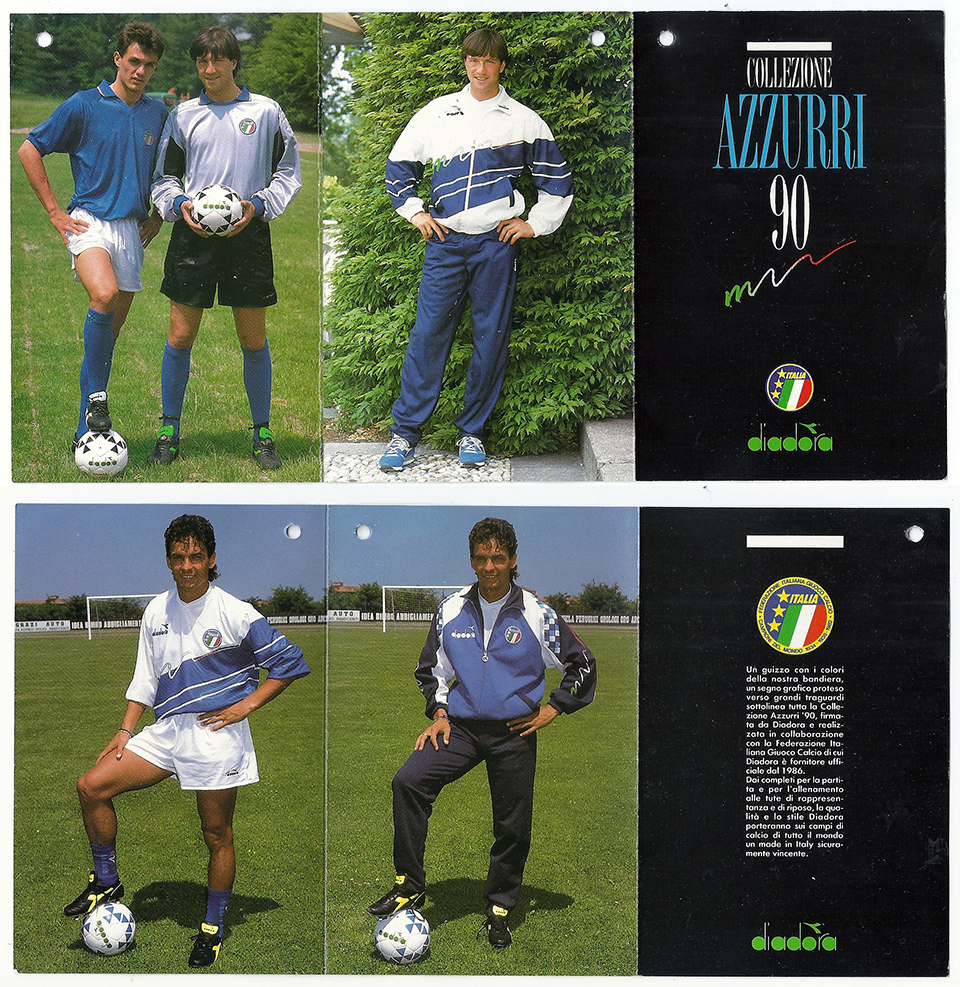

Italy 1990

Every collection has to begin somewhere, and mine began here. Prior to the 1990 World Cup my interest in football had been casual at best. I had vague recollections of Maradona’s Argentina triumphing in Mexico, but as Italia ’90 approached so my imagination and enthusiasm began to pique. I’d spent months researching the teams, players and history of the competition and avidly collecting the stickers, and I was counting the days until the tournament started. One day, while out shopping with my parents, we stopped inside a sports shop where I got to study the national team jerseys up-close for the first time. Like many young fans enamoured by the epic romance of the World Cup, my eye was first attracted to the yellow of Brazil, though the 1986 model I had admired in photographs had been replaced by the ’90 version, the updated collar of which I didn’t much care for (I finally got my hands on the ’86 shirt almost twenty years later). And so instead my attention swung to the Azzurri blue of Italy.

In hindsight it seemed the obvious choice. I’d spent the last two summers in Italy, visiting Florence, Rome and Venice, and slowly absorbing the country’s passion for calcio. Moreover, that summer Italy would be hosting the world’s greatest sporting event, and their young and exciting team was expected to go far. I walked out with a brand new Italy shirt, size XL boys (I remember it cost £19.99), and a new allegiance had been born.

Incredibly, the shirt’s design was already five years old, remaining unchanged from that used by the Azzurri at the 1986 World Cup and 1988 European Championships, which itself was essentially an updated version of the kit worn by Italy’s world champions in Spain in 1982 (which had been produced by Le Coq Sportif). This seems unthinkable today, when teams release new uniforms practically once a year. Imagine the hosts of a major tournament not cashing in on a redesigned shirt to commemorate the occasion! The only difference (that I can detect) to the 1990 incarnation, was that the already iconic tricolore stripes that ran along the edge of the collar and cuffs were inverted, meaning the red stripe was on the outside (this was only true of the players’ shirts, not of those sold commercially).

Italy opened their campaign against Austria in Rome on June 9th. It was a Saturday night: Argentina had lost to Cameroon in the opening match the day before and that afternoon I’d watched Romania beat the Soviet Union. This was my first time watching the Italian national team on live television and before kick-off it was clear from the pictures and atmosphere that there was a tremendous sense of occasion and anticipation. The Sampdoria striker Gianluca Vialli had been touted as a potential star of the tournament, and he was paired up front with Napoli’s Andrea Carnevale. Italy played at a relentlessly high tempo and were full of creativity, but were constantly thwarted by the Austrian keeper Lindenberger. I remember my mum saying how attractive some of the Italian players were and that she felt sorry for Carnevale when he was substituted with sixteen minutes remaining. His replacement was another forward, Salvatore Schillaci. The balding Sicilian had earned just one cap prior to the tournament in a friendly against Switzerland the previous March, in which he’d failed to make any impact. Few could have imagined that his late entrance would alter the course of Italy’s World Cup so dramatically. Less than two minutes later Schillaci got on the end of Vialli’s perfect cross and headed in the winning goal, to the palpable relief of a packed Stadio Olimpico.

The Italian manager Azeglio Vicini stuck by his front two for the following game with the United States. But again Carnevale failed to score, and again he was replaced by Schillaci, this time after less than an hour. Vialli didn’t fare much better, striking a first-half penalty against the post. By that time the Italians were already in front: hometown favourite Giuseppe Giannini having fired a left-foot shot past Meola after only eleven minutes. There were no further goals, but a second narrow victory against less than formidable opponents satisfied neither fans nor press. Perhaps ceding to pressure, Vicini gave Schillaci his first start in the final group match against Czechoslovakia, while an injury to Vialli prompted the coach to include Italy’s most promising star, Roberto Baggio, in the line-up. The young talent had finished the 1989-90 season as Serie A’s second-highest top scorer in a Fiorentina side that had reached the final of the UEFA Cup. Since then Baggio had become the world’s most expensive player following a controversial transfer to Juventus.

As often happens in major tournaments, Vicini had stumbled upon his best side by accident. Italy’s new attacking partnership, aided by the runs of the galloping Inter midfielder Nicola Berti, proved more than a handful for the Czech defence. Schillaci scored his second goal of the tournament (with another header) after just nine minutes. Though the Czechs were unfortunate when Griga’s perfectly good equaliser was ruled out for offside, the match is forever remembered for Baggio’s solo effort on 78 minutes. Receiving the ball on the half-way line, the young forward played a one-two with Giannini, evaded Hasek’s challenge, and after entering the area deployed a devastating feint that deceived both the last defender, Kadlec, and Stejskal in the Czech goal. Baggio was left with the relatively simple task of stroking the ball inside the near post. Italy’s new star raced away and quickly collapsed to the ground, as it perhaps dawned on him that he’d just scored one of the great World Cup goals. British commentators on both BBC and ITV coud barely contain themselves, and had to scream to be heard over the noise in the Olimpico. Over on the Italian station RAI, Bruno Pizzul seemed at a loss for words. His initial comment — “veramente bravo” — hardly did the goal justice, but as the action was replayed he happened upon a more poetic turn of phrase: “Un pezzo di antologia calcistica.”.

Having already sealed the victory with the goal of the tournament so far, Baggio’s place in the side was surely secured. More importantly, the victory meant Italy would stay in Rome to play Uruguay in the second round. Predictably, the South Americans were tough to break down, and in the second half Vicini sent on the Inter forward Aldo Serena, who would certainly provide an aerial threat. Minutes later Serena’s poked pass between Gutiérrez’s legs rolled into Schillaci’s path. As two defenders converged on him, “Totò” released an instinctive left foot shot that flew up over Alvez and under the crossbar. Italy had discovered an unlikely new hero, and no-one seemed more surprised than Schillaci himself. Arms aloft, mouth agape, eyes popping out of their sockets — his celebrations revealed nothing but joy and disbelief, that is until he was duly wrestled to the ground by a posse of delighted teammates. With five minutes left Serena nodded in a simple second — a nice thirtieth birthday present — and the Italians were through.

With the country gripped by Totòmania, the Italy team marched with confidence into its next encounter against World Cup debutantes the Republic of Ireland. The Irish squad had been granted a reception with the Pope prior to the match, but neither this nor “Big” Jack Charlton’s World Cup pedigree was enough to knock out the hosts. Almost inevitably, Schillaci was once again Italy’s goalscorer, this time with a tidy poacher’s finish after Bonner could only parry Donadoni’s drive from distance. In the second half Totò thrashed a free-kick against the crossbar that bounced onto (replays would suggest over) the line. The Azzurri had lost some of the zest they’d shown in the early games, but at this stage only the result mattered.

But in the semi-final everything changed — starting with the venue. Italy left their Roman fortress and headed south to face Maradona’s Argentina in Maradona’s Naples. Having just led Napoli to a second scudetto, Maradona now attempted to use his standing among in the city to shift local loyalties away from the hosts and towards the holders. The plan backfired, as evidenced by the banner that greeted the teams as they entered the San Paolo stadium: “DIEGO NEI CUORI, L’ITALIA NEI CORI”. Unfortunately for Italy, Vicini inexplicably tampered with his attacking tandem. Baggio was dropped to the bench, and Vialli, absent since the USA game, started in his place. Nevertheless, the Azzurri opened the scoring after nineteen minutes. Schillaci started a move on the left wing, a determined Giannini forced his way into the box, the ball fell for Vialli whose volley was blocked by Goycochea. The ball fell straight onto the toe of Totò who tapped in the rebound over the Argentine goalie. (The camera switched to a close-up of Vialli, and I remember thinking for a moment that he was the one who’d scored.)

With their noses in front, Italy were in a position to add a second. But Argentina were — for once in the tournament — playing quite well, and as the game wore on, so fear of defeat began to take hold of the Italians’ collective psyche. Deep into the second half Olarticoechea curled in a cross to the near post: Zenga arrived to meet it, but was beaten to the ball by the blond head of Caniggia, whose glanced flick floated into the far corner of the net. It was the first goal Italy had conceded in the competition so far; suddenly their involvement in the final seemed less of a certainty. Fresh legs were required: Vialli made way for Serena, but when Baggio finally came on it was at the expense of Giannini, arguably Italy’s most creative player. In extra-time Argentina’s Giusti was sent off for a supposed elbow on Baggio, the ensuing stoppages for which added a further eight minutes onto the initial fifteen! Any chance of Italy making the extra man count were scuppered immediately when Riccardo Ferri pulled up with a calf strain. Italy had already brought on both substitutes and so the poor defender had no alternative but to spend the remaining minutes hobbling around in midfield. An epic contest inched ominously towards a penalty shoot-out. Argentina had beaten Yugoslavia via spot-kicks in the previous round; for the Azzurri, it was their first experience at this level. Baresi, Serrizuela, Baggio, Burruchaga, De Agostini and Olarticoechea all scored. Then Donadoni, probably Italy’s best player on the night, saw his angled shot parried by Goycochea. Maradona (who’d missed against Yugoslavia) then tucked away Argentina’s fourth with ease. Italian hopes thus hinged on the left boot of Serena. The tall striker struck his kick hard and low, but somehow the keeper got his body behind the ball to block it on the line. The unthinkable had happened. What had seemed a certainty was suddenly an impossibility: Italy would be denied the chance to fight for a fourth world title in Rome. Instead, the superb performances of Goycochea (who’d only come into the side as a result of Pumpido’s leg fracture) had dragged Argentina to a second successive final against West Germany.

For Italy, an anti-climactic third-place match awaited them in Bari. Their opponents were England, who’d suffered an identical semi-final fate in Turin. Many neutrals — certainly English and Italian fans — felt that this pairing should have graced the final. It was certainly a much better match, and the total opposite of the uninspiring, cynical contest served up the following night. With the pressure now finally alleviated, both managers altered with their starting line-ups, which for Italy meant a rare start for Napoli defender Ciro Ferrara. The game was played in a friendly yet competitive atmosphere of mutual consolation and respect, as if both teams knew the other was still recovering from the bitter blow of a semi-final elimination.

The goals arrived in the final twenty minutes. First, Baggio sneaked in to rob the ball off a dawdling Shilton. With the aging goalkeeper beaten, he played a return pass with Schillaci and lifted the ball over a handful of desperate defenders on the line and into the net. England’s goalscoring midfielder David Platt — who would soon be playing home games at the San Nicola stadium — equalised with a bullet header from a brilliant Dorigo cross. Aside from the victory, Italy’s impetus was also to provide Schillaci with a chance to claim his sixth goal of the tournament, and thus finish as the competition’s top scorer. That opportunity arrived five minutes from the end when the Sicilian stumbled awkwardly over Parker just inside the box. Baggio — Italy’s designated penalty specialist — politely stepped aside and Totò made no mistake, leaving many to wonder what might have been had he been on Italy’s list of five penalty takers the previous Tuesday night. 2-1 would have been 3-1 had Berti’s beautifully angled header on the stroke of full-time not been incorrectly flagged for offside. Consequently Italy’s final moments of the 1990 World Cup were not crowned with one of its best goals, but rather a glaring misjudgment by a slow-witted linesman. The two squads mingled amiably on the podium as they were presented with bronze medals and bouquets. Disappointment still permeated the celebrations, but the night’s positive energy no doubt helped ease some of the pain.

A few weeks later, while on holiday in Italy, my brother and I befriended a group of children at a campsite near Venice. I’d managed to ingratiate myself to the eldest of the group, a boy named Vito from Turin, by wearing my Italy shirt. We spent several long afternoons playing football and communicating through a common love of the game. To this gang of ragazzi my blond younger brother soon became known as “Il Piccolo Gascoigne”. After we’d returned to England, a postcard arrived one day from Turin. On the front was Schillaci, smiling in his Juventus kit; on the back Vito had written “W [Viva] Totò”.

Sadly for Totò the summer of 1990 proved the beginning of the end. Vicini’s six years as coach concluded in 1991 after Italy failed to qualify for Euro 92, and the classic shirt that had characterized his tenure disappeared with him. His successor Arrigo Sacchi brought a wildly different approach to the job, and the international careers of some of Vicini’s squad — including Bergomi, Ferri, Giannini and Vialli — rapidly fizzled out. While Roberto Baggio went on to become Italian (if not world) football’s most recognizable face of the ’90s, Schillaci played his last game for the Azzurri in 1991. He soon left Juventus for Inter, and by the time the 1994 World Cup came around he was playing for Júbilo Iwata in the J-League. In recent years he has resurrected some of his fame through reality television and bit-part acting roles, while running a youth football academy in his native Palermo. Yet Totò is still forever associated with the “Notti Magiche” of 1990 when the Italians proved themselves to be, if not quite the best in the world, at least the best-dressed.

My fixation with Italia ’90 has continued into adulthood. Though the fit had become a little more snug, I wore my 1990 shirt for Italy’s games during the 2006 World Cup. I was living in Florence at the time, and watched the matches from my lucky table number five at Caffé Megara. After the Azzurri‘s victory the bar’s owner said I too deserved a medal for my superstitious devotion. Since moving to New York, thanks to eBay and some online vintage shirt specialists I’ve been able to procure more coveted items from the “Collezione Azzurri 90” range. About three years ago I bought the rarely-seen away shirt, but it was much too big and I sold it to someone in Germany — a decision I now regret. More recently, I’ve landed my hands on both of Italy’s tracksuit tops used during the 1990 tournament. The blue one was used in training while the much rarer white one (which today would be marketed as an “anthem jacket”) was worn by the team as they walked onto the pitch. I’d coveted it for twenty-four years and I still can’t quite believe the search is finally over.

Italia ’90 was the first World Cup I ever followed properly, and perhaps for this reason it remains the most special to me. Though for other reasons it marked a watershed moment in English football culture, it also represents a significant turning point in my life. Today I compare every major tournament to the 1990 World Cup, as if that were the benchmark against which all subsequent competitions must be measured. Even from an organizational and marketing point of view it hasn’t been surpassed. The abstract mascot and logos, the futuristic stadia, the use of a bed of coloured flowers to make up the team flags that displayed during the national anthems — no tournament since has quite been able to top these details. Italia ’90 was the last international tournament not to feature front numbers and names on the backs of players’ shirts, so its clean perfection simply has not been possible since. Maybe this is why Italy’s 1990 kit is still my favourite of all time.

Italy 1994

By the early 1990s the Italian national team had reached something of a turning point. While it had been an undeniably positive performance, the host nation had been disappointed with its third place finish at Italia ’90, a result from which they struggled to recover, failing to qualify for the 1992 European Championships. This crisis on the pitch perhaps provoked the most significant changes to the Azzurri kit in over a decade. That summer the FIGC unveiled a new logo, a somewhat contrived design involving a tilted rectangle and circle that awkwardly formed to create a lowercase “I”, though to most observers the device was barely apparent. The new badge was debuted with a new Diadora shirt in the summer of 1992, a design which was then further enhanced upon for the 1994 World Cup. Arrigo Sacchi’s Italy wore the new shirt for the first time in a qualifier for the tournament in late 1993 against Scotland in Rome. While still the same Azzurri blue as ever, the new logo was now interwoven into the fabric itself, creating a bizarre blue-on-blue outsized polka dot effect.

Gone were the classic tricolore striped trim which had adorned the collar and cuffs since Italy’s World Cup triumph of 1982. In their place were a series of green-white-and-red triangles, further evidence of Diadora’s new-found fixation with geometric shapes. On early versions of the shirt the triple triangle device even featured on the shirt numbers, which represented perhaps the biggest departure of all. The 3D characters which had been commonplace for much of the decade were ditched in favour of a rounded, italicized design. A similar typeface itself had been sported by the Danish national side for some time, yet in Italy’s case it came with a dark grey shadow. The new kit certainly raised eyebrows at the time of its release, though soon gained acceptance not least due to Italy’s memorable tournament in the USA. I purchased mine in April 1994 from Casa dello Sport, an extremely well-curated shop on Florence’s Via Tosinghi that carried every shirt in Serie A and B plus most international jerseys too from across Europe and South America. The entrance was cluttered with Polaroids of celebrity visitors, including Keanu Reeves and Billy Crystal. It’s hard to imagine such a place today, when most soccer jerseys are purchased online and even the best sports stores carry only the shirts of the biggest clubs.

Later that summer Italy’s World Cup campaign got off to the worst possible start: a 1-0 defeat to the Republic of Ireland at the Giants Stadium in New Jersey. In their next game against Norway things only got worse. Goalkeeper Gianluca Pagliuca received a red card in the first half for handling outside the box. In order to bring on reserve ‘keeper Luca Marchegiani, coach Arrigo Sacchi removed Roberto Baggio, much to the amazement of the watching world — and to Baggio himself. Fortunately another Baggio, the tall midfielder Dino, was on hand to head home a winner for the ten men. Later in the game Franco Baresi’s involvement in the tournament was plunged into further jeopardy after the veteran defender hobbled off with a damaged meniscus. Sacchi had been criticised before the tournament for his squad selection. Neither the young Milan full-back Christian Panucci nor an in-form Gianluca Vialli had made the cut. Now, with the competition underway, Sacchi seemed undecided, switching back and forth between Pierluigi Casiraghi and Daniele Massaro as partners for Roberto Baggio. Meanwhile, Lazio’s Giuseppe Signori — Serie A’s capocannoniere for the last two seasons — was relegated to the left of midfield. When the Azzurri faced Mexico in their final group game in Washington, D.C., Casiraghi was replaced by Massaro at half-time. The Milan forward’s first contribution was to fire Italy into the lead just two minutes later. Marcelino Bernal equalised for the Mexicans but the 1-1 draw the RFK Stadium was enough for Italy to squeeze through to the second round in third place.

It was against Nigeria in Boston that Roberto Baggio slipped into the role of Italy’s saviour. Again playing with ten men, after Gianfranco Zola’s harsh dismissal, Italy were moments away from elimination when Il Divin Codino latched onto a ball from Roberto Mussi to slot home an equaliser with seconds to spare. In extra-time Baggio got his second — a penalty which he dispatched in off the post — to secure his side’s place in the quarter-finals. I was driving through northern Italy the day the Azzurri faced Spain, and shortly after exiting the autostrada we asked the man in the toll booth the score (he had the game on a miniature TV). “Uno-zero, Dino Baggio” he responded. Indeed Dino had opened the scoring with an unstoppable drive from distance. We arrived at a bar in Serriciolo (a place I’ve written about at greater length here) to see Spain gain the upper hand in the second half, equalising through José Caminero. Only a last-ditch save by Pagliuca (with his feet) and and a brilliant tackle by Alessandro Costacurta prevented Italy from going behind. For efficiency and to avoid confusion RAI commentator Bruno Pizzul had taken to referring to the two Baggios by their first names only, so maybe I’ll do the same here. Extra-time loomed, when Signori reached Nicola Berti’s chipped ball and lofted a pass beyond the last Spanish defender and into Roberto’s path. The Juventus forward beat Zubizarreta to the ball, took it wide of the Spanish goalkeeper and slotted home from the a tight angle under the stretching leg of Abelardo. Once again Italy had left it late, but there was still time for Mauro Tassotti to fling a vicious elbow into the face of Luis Enrique. After the game, the 34-year-old defender received a nine-match ban, effectively ending his Italy career. Had the referee spotted the incident, it would have resulted in a certain penalty for Spain.

We returned to the bar for the semi-final, for which Italy returned to the Giants Stadium. Their unlikely opponents were Bulgaria, who had knocked out the holders Germany in dramatic fashion in the previous round. It was the match in which the Azzurri gave their best performance of the tournament, producing a first-half display of fluid attacking football rarely seen at such a level. What a contrast from four years earlier, when the pressure on the Italians to win at home had stifled their attacking instincts. Inevitably, Roberto opened the scoring with a beautiful solo effort, hurdling two defenders before calmly curling the ball into Boris Mikhailov’s far corner. Milan’s Demetrio Albertini was pulling all the strings in midfield, striking the post with an terrific angled shot, then seconds later prompting a fine save from Mikhailov with a deft chip. Roberto met Albertini’s dinked ball into the box from the resulting corner, and fired in a neat shot for his and Italy’s second. Bulgaria’s Hristo Stoichkov pulled a goal back — his sixth of the tournament — from the penalty spot before half-time, but Italy held on for their third consecutive 2-1 victory. But there was bad news in store for Italy: Costacurta’s yellow card ruled himself out of the final. Remarkably, Baresi — who had missed the last four games after undergoing surgery two weeks earlier — returned to the side to take his place.

Italy’s two-goal was replaced in the second half, officially to rest for the final in Pasadena, but his tears and precautionary ice-pack suggested an injury. The 26-year-old was at the peak of his career, having won a UEFA Cup and Ballon d’Or the previous year. Now he had embarked on embarked on a one-man, three-match, five-goal crusade that culminated with a berth in the World Cup Final against Brazil, the likelihood of which had seemed highly improbable just two weeks earlier. His performances in the latter stages of the competition recalled those of Paolo Rossi’s in 1982: both players had shaken off indifferent early results to come up with vital goals at just the right moment. Yet while Rossi’s good run continued through to the final, a clearly unfit Baggio was left to hobble about the Rose Bowl in the midday sun, his thigh heavily strapped.

For the final the bar moved its television set outside into the car park and set up rows of seats for locals to come and watch. I sat wearing my new Italy shirt holding a tricolore flag on a stick which I’d bought six years earlier in Siena. I was one of my most memorable football viewing experiences, surrounded by a small town of nervous and excited Italian strangers, our faces bathed in the glow of the screen. I remember the local boys chanting “Cafú, tu sei un figlio di puttana!” after the full-back came on for the injured Jorginho. The 1994 final is often recalled as a negative, even boring final, probably because it ended goalless after 120 minutes. But the game was not without incident, and poor finishing by both sides was the only reason the contest went to the wire. Romário, Bebeto and Massaro all missed good chances, and Roberto squandered an opportunity he would have probably buried a few days earlier. Both sides resorted to long-range efforts in extra-time, except for Brazilian substitute Viola, whose skillful run almost resulted in a fantastic winning goal. And so a World Cup final was decided by a penalty shoot-out for the first time, a most unsatisfactory climax to what had generally been a highly entertaining tournament.

Italian hopes were restored when Pagliuca saved from Marcio Santos following Baresi’s initial miss. Then Albertini, Romário, Evani and Branco all scored. Taffarel saved from Massaro’s fourth kick and then Brazilian captain Dunga scored, putting all the pressure on Italy’s five-goal hero Roberto Baggio, who launched his tired shot into the skies of Southern California. I can still remember Pizzul’s typically understated utterance the moment Brazil were crowned world champions for a record fourth time: “Alto. Il campionato del mondo è finito.” I’d felt a strong connection to the Azzurri since the previous World Cup in Italy, and when Baggio’s last penalty sailed over the bar those feelings grew even deeper. Women and children were in tears, and powerless ragazzi began hurling plastic and wooden chairs over the fence and onto the train tracks out of sheer frustration. For the next few days the atmosphere was one of a nation in mourning.

From that point on I always felt that Baggio seemed to carry an air of melancholia, as if a part of him had remained forever rooted to that penalty spot in Pasadena. “Penalties are missed only by those who dare take them,” he would say, almost as if it were a mantra he was using to get over the trauma. Through the rest of the decade Baggio’s involvement with the national team would become more sporadic. Italy flopped at Euro ’96 and lost again on penalties to the hosts at France ’98 (although this time Baggio scored his kick). The quirky “I” logo was finally removed from the Azzurri shirt in 1999 and replaced with the classic tricolore badge sported throughout the sixties and seventies, as football design became increasingly influenced by its past in the new millennium. Subsequent Italy coaches including Dino Zoff and Giovanni Trapattoni were reluctant to recall Baggio to the team, citing age, fitness concerns and club form as reasons to leave him out. After not making the squads for the 2002 World Cup nor Euro 2004 despite huge public demand, Baggio was given an international send-off in a friendly against Spain in Genoa, a match that marked his 56th cap. No Italian player had been honoured in this way since Silvio Piola, but to me it seemed appropriate. Whether it was because he was denied football’s ultimate prize in the cruellest manner possible, or because this pony-tailed Buddhist was such an unconventional Italian hero, his popularity had never faded. Having represented Vicenza, Fiorentina, Juventus, Milan, Bologna, Inter and Brescia, Baggio always seemed to belong more to the national team than to any one club side.

Milan 1990-91

Success was so swift and so absolute for Silvio Berlusconi’s Milan, that it’s easy to forget when he had taken over the presidency the once prestigious club found itself ridden in debt, having spent two seasons in Serie B in the early 1980s. Though the team already boasted some talented local youngsters including Baresi, Maldini, Donadoni and Evani, their foreign stars were aging. Milan lacked that special player — a Maradona or a Platini — necessary to make the extra leap to domestic and European glory. In the summer of 1987 Berlusconi’s finances (funded at the time by his growing media empire) helped secure the talents of young Dutch stars Ruud Gullit and Marco Van Basten. That season Milan pipped Champions Napoli to the Serie A title, their first scudetto in nine years. Later that summer Gullit and Van Basten proved instrumental in Holland’s first major trophy, the European Championship, and after the tournament their international teammate, Frank Rijkaard, joined them at Milan.

Berlusconi’s influence was not only economical. He insisted his side produce attractive, attacking football, and his power wielded an unprecedented control over transfers, team selection and technical aspects of the side’s preparation. In Arrigo Sacchi he found the ideal coach, an eccentric but brilliant man, who, despite fielding an imperviously strong back four, represented the antithesis of catenaccio. By the end of the decade Milan were once again the dominant force in Europe, winning back-to-back European Cups in 1989 and 1990, a trophy which had eluded them for twenty years. They topped those victories off on both occasions with successive triumphs in the Intercontinental Cup in Tokyo.

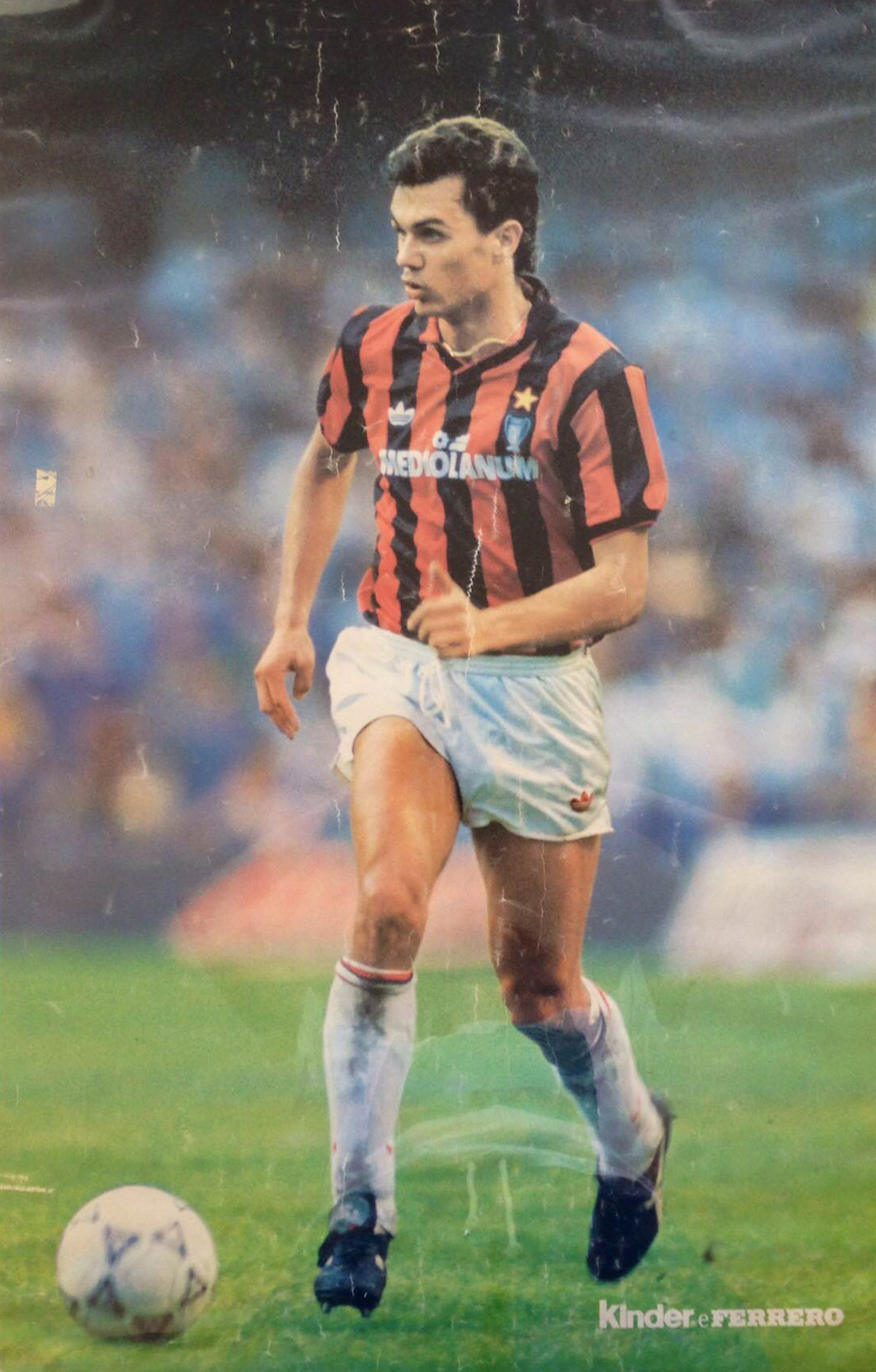

Through regular visits to Italy and my burgeoning fixation with calcio I’d become fascinated by Sacchi’s Milan side, and in 1991 I bought the famous maglia rossonera from a store in the northern Tuscan town of Aulla. Given the quality of its domestic league football in Italy was remarkably uncommercialised in those days. All the shirts in the shop were folded in their manufacturers’ plastic wrappers and stacked up to the ceiling; after inquiring about the Milan kit a lady climbed to the top of a ladder to retrieve my size. The shirt was only available with long-sleeves, which seemed impractical to me at the time (it was July) but wholly appropriate once I recalled images of San Siro shrouded in a thick fog, the rossoneri carving out victories from its frosty turf.

Milan had changed kit manufacturer in 1990, switching from Kappa to adidas, but the shirt had remained essentially unchanged for the last four years. The sponsor was still Mediolanum, Berlusconi’s own insurance company, named for the Latin word for Milan (the city). Above it on the right was the gold star which is earned after ten scudetto wins, beneath which sat an embroidered European Cup celebrating the fact that Milan were the current holders of that trophy (a nice initiative which never caught on). In the 1990-91 season Milan finished second in Serie A, a full five points behind scudetto winners Sampdoria, to whom they lost twice. A defeat to lowly Bari in the penultimate match of the season effectively ended their title hopes.

Milan’s good domestic showing was marred by a disastrous European Cup campaign. The rossoneri were aiming for a record-equalling third straight triumph in the competition, and came up against a talented Olympique Marseille team in the quarter-final. The first leg at San Siro ended 1-1; in the return match Chris Waddle had given the French champions the lead on 75 minutes when deep into injury time the floodlights at the Stade Velodrome failed. When power was restored after several minutes Milan refused to return to the pitch – a gesture which most interpreted as a desperate attempt to seize the opportunity for a rematch. Either way the tactic backfired: UEFA awarded a 3-0 result to Marseille, while Milan were banned from all European competition for the 1991-92 season.

His time at Milan having clearly run its course, Arrigo Sacchi left the rossoneri that summer to take over the Italian national team. Under his replacement, Fabio Capello, Milan galloped to a record-breaking Serie A season, becoming the first side to win lo scudetto without defeat. Van Basten finished the season as top scorer with 25 goals. The shirt remained unchanged from the previous season, although since Milan were no longer holders of the European Cup, its presence on the shirt was replaced by the Intercontinental Cup; when Red Star Belgrade took this title away from them in December 1991 they reverted to a traditional Milan logo (incidentally the first appearance of the club crest on the rossoneri jersey).

Milan collected three successive Serie A titles with Capello at the helm, and with success on the pitch changes to the kit remained subtle over the next few seasons. In 1992 a new sponsor arrived in the form of local dessert company Motta, and the following year a new kit deal was launched with the Italian sportswear manufacturer Lotto. Milan re-established their relationship with adidas in 1998, by which time they’d begun a long-term sponsorship by the German car giant Opel.

As Berlusconi ventured into politics his desire to create a European supersquad had resulted in the arrival of some big names — Savicevic, Boban, Papin, Raducioiu, Lentini — all of whom now competed for positions in Milan’s line-up. As Capello struggled with the challenge of keeping his bloated roster of big names happy, the Dutch trio’s dominance became undermined and was effectively broken up. The last time the three played together was the 1993 European Cup final in Munich, a 1-0 defeat by old rivals Marseille. That summer Rijkaard returned to Ajax and Gullit unexpectedly left for Sampdoria. Van Basten stayed at Milan, unaware he’d already played the last game of his career. He remained on the sidelines throughout the 1993-94 season, missing out on the team’s European Cup triumph and that summer’s World Cup, before finally announcing his official retirement in 1995 at the age of 30.

The same summer I bought my Milan shirt I also obtained a giant poster of a young Paolo Maldini wearing the same kit. It was free from the local supermarket in exchange for the purchase of several packets of apricot jam-filled Kinder brioche (my brother got Baggio). Something about the lighting always made me believe the photo was taken at the San Paolo in Naples (the ball is correct, Paolino wore short-sleeves in that fixture, and there’s clearly an ad for Mars in the background). Either way the poster hung pinned on my bedroom wall for over a decade, and now hangs framed in my apartment in New York, just feet from where I sit as I write this. A few years ago adidas relaunched the 1990-91 shirt as a limited edition replica, presumably for fans who now regretted not getting their hands on it the first time. Yet somehow the remake wasn’t quite the same. The sponsor was too large and the slightly bulbous adidas logo had been corrected. The material was too glossy, too well-made. It was as if the memories of both the shirt’s manufacturer and its consumer had been warped by the team’s own legend. Milan weren’t perfect, and nor was their shirt. But both came mighty close.

Palmeiras 1990-91

Coming soon…