Every collection has to begin somewhere, and mine began here. Prior to the 1990 World Cup my interest in football had been casual at best. I had vague recollections of Maradona’s Argentina triumphing in Mexico, but as Italia ’90 approached so my imagination and enthusiasm began to pique. I’d spent months researching the teams, players and history of the competition and avidly collecting the stickers, and I was counting the days until the tournament started. One day, while out shopping with my parents, we stopped inside a sports shop where I got to study the national team jerseys up-close for the first time. Like many young fans enamoured by the epic romance of the World Cup, my eye was first attracted to the yellow of Brazil, though the 1986 model I had admired in photographs had been replaced by the ’90 version, the updated collar of which I didn’t much care for (I finally got my hands on the ’86 shirt almost twenty years later). And so instead my attention swung to the Azzurri blue of Italy.

In hindsight it seemed the obvious choice. I’d spent the last two summers in Italy, visiting Florence, Rome and Venice, and slowly absorbing the country’s passion for calcio. Moreover, that summer Italy would be hosting the world’s greatest sporting event, and their young and exciting team was expected to go far. I walked out with a brand new Italy shirt, size XL boys (I remember it cost £19.99), and a new allegiance had been born.

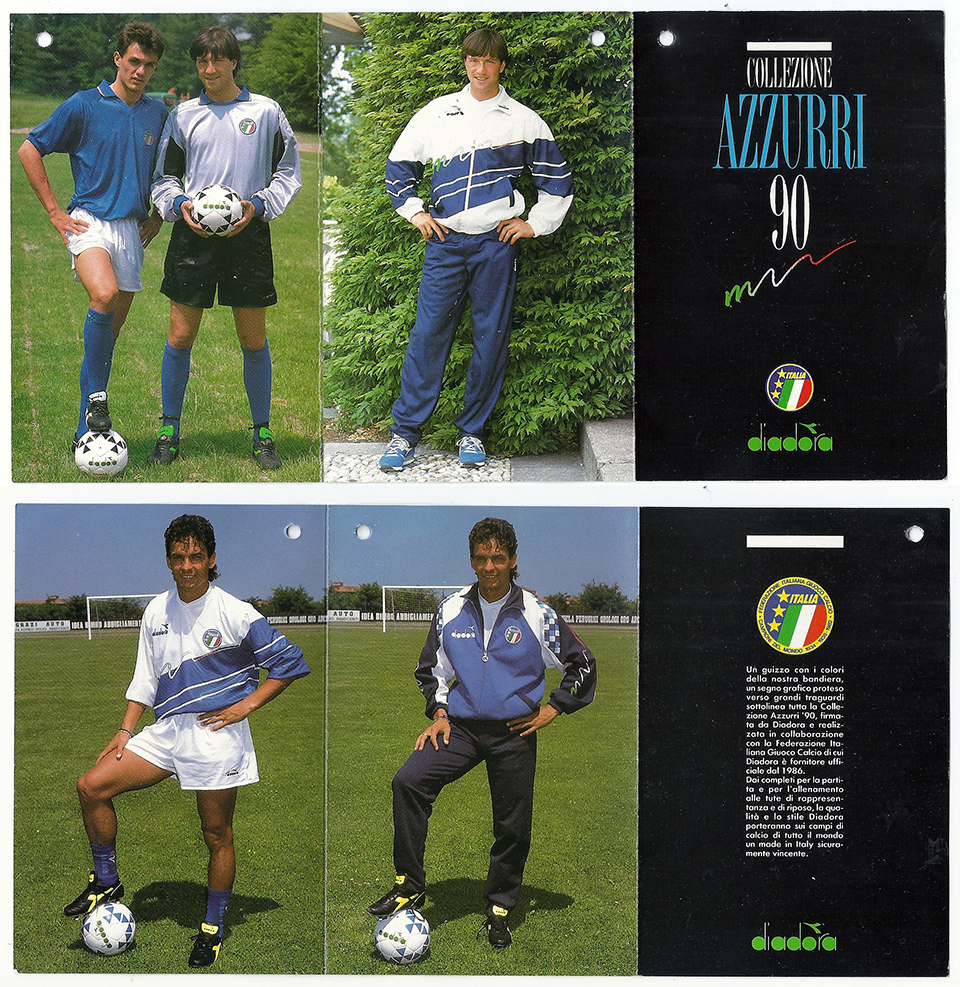

Incredibly, the shirt’s design was already five years old, remaining unchanged from that used by the Azzurri at the 1986 World Cup and 1988 European Championships, which itself was essentially an updated version of the kit worn by Italy’s world champions in Spain in 1982 (which had been produced by Le Coq Sportif). This seems unthinkable today, when teams release new uniforms practically once a year. Imagine the hosts of a major tournament not cashing in on a redesigned shirt to commemorate the occasion! The only difference (that I can detect) to the 1990 incarnation, was that the already iconic tricolore stripes that ran along the edge of the collar and cuffs were inverted, meaning the red stripe was on the outside (this was only true of the players’ shirts, not of those sold commercially).

Italy opened their campaign against Austria in Rome on June 9th. It was a Saturday night: Argentina had lost to Cameroon in the opening match the day before and that afternoon I’d watched Romania beat the Soviet Union. This was my first time watching the Italian national team on live television and before kick-off it was clear from the pictures and atmosphere that there was a tremendous sense of occasion and anticipation. The Sampdoria striker Gianluca Vialli had been touted as a potential star of the tournament, and he was paired up front with Napoli’s Andrea Carnevale. Italy played at a relentlessly high tempo and were full of creativity, but were constantly thwarted by the Austrian keeper Lindenberger. I remember my mum saying how attractive some of the Italian players were and that she felt sorry for Carnevale when he was substituted with sixteen minutes remaining. His replacement was another forward, Salvatore Schillaci. The balding Sicilian had earned just one cap prior to the tournament in a friendly against Switzerland the previous March, in which he’d failed to make any impact. Few could have imagined that his late entrance would alter the course of Italy’s World Cup so dramatically. Less than two minutes later Schillaci got on the end of Vialli’s perfect cross and headed in the winning goal, to the palpable relief of a packed Stadio Olimpico.

The Italian manager Azeglio Vicini stuck by his front two for the following game with the United States. But again Carnevale failed to score, and again he was replaced by Schillaci, this time after less than an hour. Vialli didn’t fare much better, striking a first-half penalty against the post. By that time the Italians were already in front: hometown favourite Giuseppe Giannini having fired a left-foot shot past Meola after only eleven minutes. There were no further goals, but a second narrow victory against less than formidable opponents satisfied neither fans nor press. Perhaps ceding to pressure, Vicini gave Schillaci his first start in the final group match against Czechoslovakia, while an injury to Vialli prompted the coach to include Italy’s most promising star, Roberto Baggio, in the line-up. The young talent had finished the 1989-90 season as Serie A’s second-highest top scorer in a Fiorentina side that had reached the final of the UEFA Cup. Since then Baggio had become the world’s most expensive player following a controversial transfer to Juventus.

As often happens in major tournaments, Vicini had stumbled upon his best side by accident. Italy’s new attacking partnership, aided by the runs of the galloping Inter midfielder Nicola Berti, proved more than a handful for the Czech defence. Schillaci scored his second goal of the tournament (with another header) after just nine minutes. Though the Czechs were unfortunate when Griga’s perfectly good equaliser was ruled out for offside, the match is forever remembered for Baggio’s solo effort on 78 minutes. Receiving the ball on the half-way line, the young forward played a one-two with Giannini, evaded Hasek’s challenge, and after entering the area deployed a devastating feint that deceived both the last defender, Kadlec, and Stejskal in the Czech goal. Baggio was left with the relatively simple task of stroking the ball inside the near post. Italy’s new star raced away and quickly collapsed to the ground, as it perhaps dawned on him that he’d just scored one of the great World Cup goals. British commentators on both BBC and ITV coud barely contain themselves, and had to scream to be heard over the noise in the Olimpico. Over on the Italian station RAI, Bruno Pizzul seemed at a loss for words. His initial comment — “veramente bravo” — hardly did the goal justice, but as the action was replayed he happened upon a more poetic turn of phrase: “Un pezzo di antologia calcistica.”.

Having already sealed the victory with the goal of the tournament so far, Baggio’s place in the side was surely secured. More importantly, the victory meant Italy would stay in Rome to play Uruguay in the second round. Predictably, the South Americans were tough to break down, and in the second half Vicini sent on the Inter forward Aldo Serena, who would certainly provide an aerial threat. Minutes later Serena’s poked pass between Gutiérrez’s legs rolled into Schillaci’s path. As two defenders converged on him, “Totò” released an instinctive left foot shot that flew up over Alvez and under the crossbar. Italy had discovered an unlikely new hero, and no-one seemed more surprised than Schillaci himself. Arms aloft, mouth agape, eyes popping out of their sockets — his celebrations revealed nothing but joy and disbelief, that is until he was duly wrestled to the ground by a posse of delighted teammates. With five minutes left Serena nodded in a simple second — a nice thirtieth birthday present — and the Italians were through.

With the country gripped by Totòmania, the Italy team marched with confidence into its next encounter against World Cup debutantes the Republic of Ireland. The Irish squad had been granted a reception with the Pope prior to the match, but neither this nor “Big” Jack Charlton’s World Cup pedigree was enough to knock out the hosts. Almost inevitably, Schillaci was once again Italy’s goalscorer, this time with a tidy poacher’s finish after Bonner could only parry Donadoni’s drive from distance. In the second half Totò thrashed a free-kick against the crossbar that bounced onto (replays would suggest over) the line. The Azzurri had lost some of the zest they’d shown in the early games, but at this stage only the result mattered.

But in the semi-final everything changed — starting with the venue. Italy left their Roman fortress and headed south to face Maradona’s Argentina in Maradona’s Naples. Having just led Napoli to a second scudetto, Maradona now attempted to use his standing among in the city to shift local loyalties away from the hosts and towards the holders. The plan backfired, as evidenced by the banner that greeted the teams as they entered the San Paolo stadium: “DIEGO NEI CUORI, L’ITALIA NEI CORI”. Unfortunately for Italy, Vicini inexplicably tampered with his attacking tandem. Baggio was dropped to the bench, and Vialli, absent since the USA game, started in his place. Nevertheless, the Azzurri opened the scoring after nineteen minutes. Schillaci started a move on the left wing, a determined Giannini forced his way into the box, the ball fell for Vialli whose volley was blocked by Goycochea. The ball fell straight onto the toe of Totò who tapped in the rebound over the Argentine goalie. (The camera switched to a close-up of Vialli, and I remember thinking for a moment that he was the one who’d scored.)

With their noses in front, Italy were in a position to add a second. But Argentina were — for once in the tournament — playing quite well, and as the game wore on, so fear of defeat began to take hold of the Italians’ collective psyche. Deep into the second half Olarticoechea curled in a cross to the near post: Zenga arrived to meet it, but was beaten to the ball by the blond head of Caniggia, whose glanced flick floated into the far corner of the net. It was the first goal Italy had conceded in the competition so far; suddenly their involvement in the final seemed less of a certainty. Fresh legs were required: Vialli made way for Serena, but when Baggio finally came on it was at the expense of Giannini, arguably Italy’s most creative player. In extra-time Argentina’s Giusti was sent off for a supposed elbow on Baggio, the ensuing stoppages for which added a further eight minutes onto the initial fifteen! Any chance of Italy making the extra man count were scuppered immediately when Riccardo Ferri pulled up with a calf strain. Italy had already brought on both substitutes and so the poor defender had no alternative but to spend the remaining minutes hobbling around in midfield. An epic contest inched ominously towards a penalty shoot-out. Argentina had beaten Yugoslavia via spot-kicks in the previous round; for the Azzurri, it was their first experience at this level. Baresi, Serrizuela, Baggio, Burruchaga, De Agostini and Olarticoechea all scored. Then Donadoni, probably Italy’s best player on the night, saw his angled shot parried by Goycochea. Maradona (who’d missed against Yugoslavia) then tucked away Argentina’s fourth with ease. Italian hopes thus hinged on the left boot of Serena. The tall striker struck his kick hard and low, but somehow the keeper got his body behind the ball to block it on the line. The unthinkable had happened. What had seemed a certainty was suddenly an impossibility: Italy would be denied the chance to fight for a fourth world title in Rome. Instead, the superb performances of Goycochea (who’d only come into the side as a result of Pumpido’s leg fracture) had dragged Argentina to a second successive final against West Germany.

For Italy, an anti-climactic third-place match awaited them in Bari. Their opponents were England, who’d suffered an identical semi-final fate in Turin. Many neutrals — certainly English and Italian fans — felt that this pairing should have graced the final. It was certainly a much better match, and the total opposite of the uninspiring, cynical contest served up the following night. With the pressure now finally alleviated, both managers altered with their starting line-ups, which for Italy meant a rare start for Napoli defender Ciro Ferrara. The game was played in a friendly yet competitive atmosphere of mutual consolation and respect, as if both teams knew the other was still recovering from the bitter blow of a semi-final elimination.

The goals arrived in the final twenty minutes. First, Baggio sneaked in to rob the ball off a dawdling Shilton. With the aging goalkeeper beaten, he played a return pass with Schillaci and lifted the ball over a handful of desperate defenders on the line and into the net. England’s goalscoring midfielder David Platt — who would soon be playing home games at the San Nicola stadium — equalised with a bullet header from a brilliant Dorigo cross. Aside from the victory, Italy’s impetus was also to provide Schillaci with a chance to claim his sixth goal of the tournament, and thus finish as the competition’s top scorer. That opportunity arrived five minutes from the end when the Sicilian stumbled awkwardly over Parker just inside the box. Baggio — Italy’s designated penalty specialist — politely stepped aside and Totò made no mistake, leaving many to wonder what might have been had he been on Italy’s list of five penalty takers the previous Tuesday night. 2-1 would have been 3-1 had Berti’s beautifully angled header on the stroke of full-time not been incorrectly flagged for offside. Consequently Italy’s final moments of the 1990 World Cup were not crowned with one of its best goals, but rather a glaring misjudgment by a slow-witted linesman. The two squads mingled amiably on the podium as they were presented with bronze medals and bouquets. Disappointment still permeated the celebrations, but the night’s positive energy no doubt helped ease some of the pain.

A few weeks later, while on holiday in Italy, my brother and I befriended a group of children at a campsite near Venice. I’d managed to ingratiate myself to the eldest of the group, a boy named Vito from Turin, by wearing my Italy shirt. We spent several long afternoons playing football and communicating through a common love of the game. To this gang of ragazzi my blond younger brother soon became known as “Il Piccolo Gascoigne”. After we’d returned to England, a postcard arrived one day from Turin. On the front was Schillaci, smiling in his Juventus kit; on the back Vito had written “W [Viva] Totò”.

Sadly for Totò the summer of 1990 proved the beginning of the end. Vicini’s six years as coach concluded in 1991 after Italy failed to qualify for Euro 92, and the classic shirt that had characterized his tenure disappeared with him. His successor Arrigo Sacchi brought a wildly different approach to the job, and the international careers of some of Vicini’s squad — including Bergomi, Ferri, Giannini and Vialli — rapidly fizzled out. While Roberto Baggio went on to become Italian (if not world) football’s most recognizable face of the ’90s, Schillaci played his last game for the Azzurri in 1991. He soon left Juventus for Inter, and by the time the 1994 World Cup came around he was playing for Júbilo Iwata in the J-League. In recent years he has resurrected some of his fame through reality television and bit-part acting roles, while running a youth football academy in his native Palermo. Yet Totò is still forever associated with the “Notti Magiche” of 1990 when the Italians proved themselves to be, if not quite the best in the world, at least the best-dressed.

My fixation with Italia ’90 has continued into adulthood. Though the fit had become a little more snug, I wore my 1990 shirt for Italy’s games during the 2006 World Cup. I was living in Florence at the time, and watched the matches from my lucky table number five at Caffé Megara. After the Azzurri‘s victory the bar’s owner said I too deserved a medal for my superstitious devotion. Since moving to New York, thanks to eBay and some online vintage shirt specialists I’ve been able to procure more coveted items from the “Collezione Azzurri 90” range. About three years ago I bought the rarely-seen away shirt, but it was much too big and I sold it to someone in Germany — a decision I now regret. More recently, I’ve landed my hands on both of Italy’s tracksuit tops used during the 1990 tournament. The blue one was used in training while the much rarer white one (which today would be marketed as an “anthem jacket”) was worn by the team as they walked onto the pitch. I’d coveted it for twenty-four years and I still can’t quite believe the search is finally over.

Italia ’90 was the first World Cup I ever followed properly, and perhaps for this reason it remains the most special to me. Though for other reasons it marked a watershed moment in English football culture, it also represents a significant turning point in my life. Today I compare every major tournament to the 1990 World Cup, as if that were the benchmark against which all subsequent competitions must be measured. Even from an organizational and marketing point of view it hasn’t been surpassed. The abstract mascot and logos, the futuristic stadia, the use of a bed of coloured flowers to make up the team flags that displayed during the national anthems — no tournament since has quite been able to top these details. Italia ’90 was the last international tournament not to feature front numbers and names on the backs of players’ shirts, so its clean perfection simply has not been possible since. Maybe this is why Italy’s 1990 kit is still my favourite of all time.