In the summer of 1990 Fiorentina entered a new era. Having just suffered their worst Serie A finish in over a decade under Italian World Cup-winner Francesco Graziani, it was then revealed that Roberto Baggio would be sold to Juventus for a world record 25 billion lire. The transfer of la Viola‘s star player to its bitterest rivals provoked violent protests on the streets of Florence, coming just two days after Juventus had beaten Fiorentina in the UEFA Cup Final. Even Fiorentina’s headquarters in Piazza Savonarola came under attack, duly prompting the club’s owners, the Pontello family, to hand over operations to film producer Mario Cecchi Gori.

The team failed to improve in its first season without Baggio, for which Cecchi Gori immediately attempted to make amends. In what was undoubtedly the most significant business deal of his presidency, Cecchi Gori signed young Argentine forward Gabriel Batistuta. The dashing striker had just helped lead his country to victory in the Copa America in Chile, after having scored thirteen goals for Boca Juniors the previous season. He continued this impressive scoring rate in Italy, finding the net thirteen times in his debut season in Serie A. But despite Batistuta’s goals Fiorentina still failed to challenge the league leaders, finishing a mediocre twelfth for a third successive campaign. In the summer of 1992 it was hoped that the arrival of blond German midfielder Stefan Effenberg and elegant Danish winger Brian Laudrup — the latter a freshly-crowned European Champion — would make the difference.

Luigi Radice, who’d coached Fiorentina to sixth place in 1974, was again at the helm, having replaced Brazilian Sebastiano Lazaroni early in the 1991-92 season. His team started slowly, drawing three of its first four games. Although goals were easy to come by — Fiorentina put seven past a hapless Ancona in week three — keeping them out at the other end proved more difficult, and after five games they’d already conceded thirteen goals, seven of which came at home against a ruthless Milan side. The team from Florence responded well to this setback but impressive victories against Sampdoria, Roma and even Juventus were countered by defeats to Cagliari, Napoli and Atalanta. This loss at home to the side from Bergamo proved Radice’s last in charge, and he was replaced by another former Viola coach, Aldo Agroppi.

At the time of Radice’s sacking Fiorentina were in a respectable sixth in Serie A. By the time Agroppi was let go following a 3-0 hammering at Juventus, the team had plunged towards the relegation zone, having racked up just two victories (against Pescara and Cagliari) under his reign. With just five games remaining former striker Luciano Chiarugi was handed the unenviable task of rescuing Fiorentina’s season. But the damage had already been done, and three more draws and a defeat against Atalanta left the team in the drop zone. Yet la Viola were still in with a chance of avoiding disaster as they went into their final game, in which they played host to Foggia. By half-time the home side had galloped into a four-goal lead and looked to have made themselves safe, despite fellow strugglers Brescia winning at Sampdoria. But with ten minutes of the season remaining, Udinese midfielder Stefano Desideri’s spectacular equaliser against Roma lifted his side above Fiorentina, whose fate was suddenly taken out of their own hands. There was still time for more late goals in Florence (the game finished 6-2) but the final minutes were played in a funereal atmosphere. Despite finishing with the same points total as Brescia and Udinese, and just six points behind seventh-placed Sampdoria, the unthinkable had become a reality: Fiorentina were relegated to Serie B after fifty-four consecutive years in the top flight.

The man asked to lead the club back to Serie A was Claudio Ranieri. The former Napoli coach decided that Serie B was the perfect place to thrust a handful of promising youth talents — including goalkeeper Francesco Toldo and forwards Anselmo Robbiati and Francesco Flachi — into the first team. These additions joined an already strong squad. Although Laudrup was quickly offloaded to Italian champions Milan, the rest of Fiorentina’s players seemed content to help the side out of the mess in which it now found itself. Batistuta and Effenberg were commended for showing such loyalty at the risk of losing their places in their respective national sides, and in a World Cup year no less. The Argentine, now known by the Florentine faithful as “Batigol”, again found the net sixteen times during the 1993-94 campaign, atop a scoring chart that also included future Serie A legends Oliver Bierhoff (Ascoli), Enrico Chiesa (Modena), Filippo Inzaghi (Verona) and Christian Vieri (Ravenna).

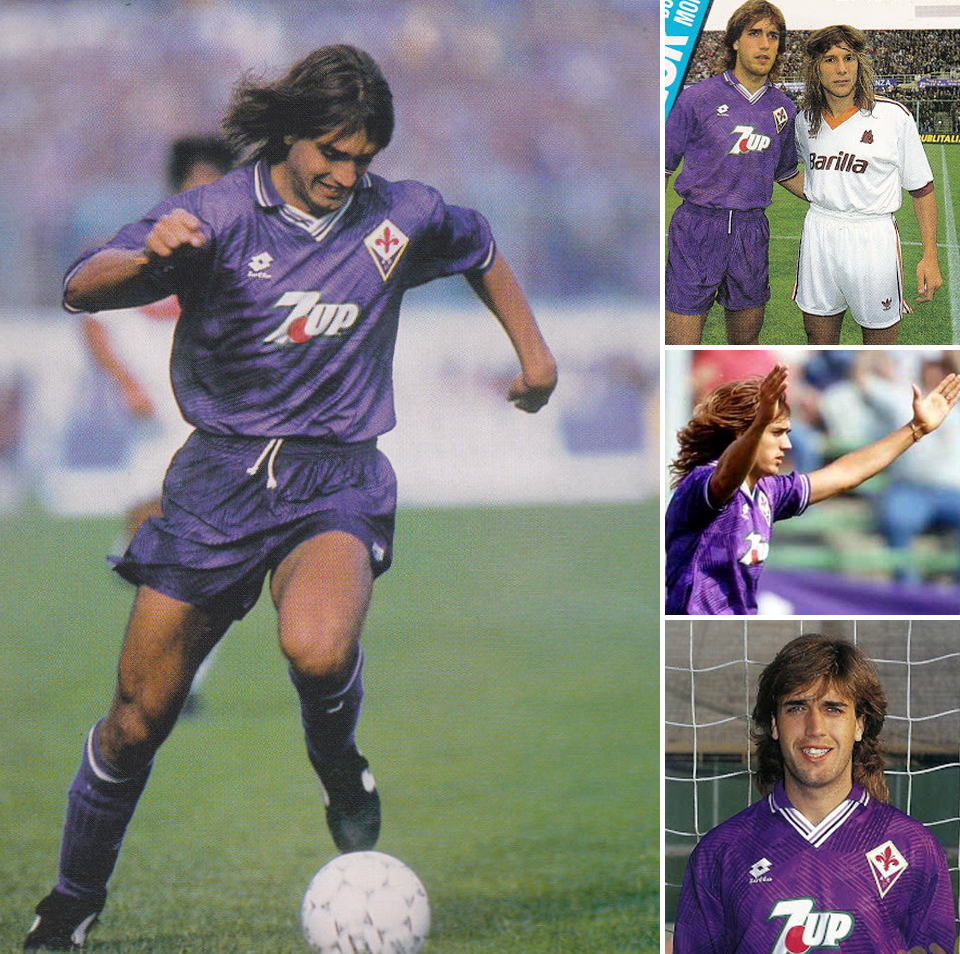

Fiorentina’s kit from 1991 to 1993 was produced by Lotto, in a design that matched the template worn by the Dutch national team in the same period. In 1991 the club ditched the stylised “F” logo reverted to a traditional kite-shape crest. In 1992 the shirt saw small modifications to the collar and sponsor, which changed from Giocheria (an Italian toy company) to the internationally-recognised soft drink 7-Up. It was Fiorentina’s away shirt that season that drew most attention for its unfortunate swastika-like motif hidden within the purple pattern across the sleeves and shoulders. The shirt was worn in four away games before the now infamous design flaw was pointed out, after which la Viola reverted to a plain white strip. I bought the 1992-93 home shirt from Casa dello Sport, a veritable mecca for football shirt enthusiasts located in Via de’ Tosinghi in the heart of Florence’s centro storico (I later picked up the shorts and socks to match). Fiorentina kept the same look during their season spent in Serie B, although the kit was now manufactured by the German company Uhlsport. When the side returned to Serie A in 1994 a new sponsorship deal was struck with Tuscan ice cream company Sammontana.

My first ever visit to the Stadio Artemio Franchi occurred while la Viola‘s were languishing in Serie B, in a league fixture against Modena in April 1994. The match was played under a torrential downpour; ironically Fiorentina’s free-flowing goalscoring form had completely dried up, and the game finished goalless. Nevertheless, in the end Fiorentina bounced back to Serie A comfortably, eventually finishing on top of Serie B, five points ahead of second-placed Bari. Sadly Mario Cecchi Gori didn’t live to see the side gain promotion, having died in late 1993, at which point the club was taken over by his son, Vittorio. With Effenberg returning to Borussia Mönchengladbach following promotion, the club now needed to bolster their squad if they were to make an impact in Serie A. Brazilian Marcio Santos arrived from Bordeaux, having just won the World Cup in the United States. But the central defender’s time in Florence was brief, and he moved on to Ajax after a single season in Italy. Fiorentina’s other big signing fared a little better. Manuel Rui Costa had broken into Benfica’s first team as a teenager and was already an established name in the Portuguese national side. To the delight of the Viola fans, the young Portuguese playmaker developed an immediate understanding with Batistuta, who found the net in the first eleven games of the season, beating a record held since the 1950s by Ezio Pascutti of Bologna. With his twenty-six strikes that season, the Argentine also equalled Kurt Hamrin’s record of most goals scored by a Fiorentina player in a single league campaign. But despite “Batigol” more than living up to his nickname, and Rui Costa’s emergence as one of Serie A’s finest number tens scoring, Fiorentina’s form began to slip after the new year, and they eventually finished a disappointing tenth, failing to qualify even for the UEFA Cup.

Yet the disappointment was tempered with the fact that Fiorentina had finally turned a corner. The nightmare of relegation was behind them, and in Batistuta they’d found a new hero to take over the mantle of Baggio. Over the next few seasons Fiorentina continued to grow stronger, with Batistuta, Rui Costa and Toldo remaining key men in a side that ultimately began to challenge for top honours at home and in Europe. But just when it seemed the club was enjoying its best spell in years, so the fun came to an abrupt halt. The 1990s had been certainly been a rollercoaster of a decade for Fiorentina, but it was nothing compared to what was to come, as la Viola entered the most turbulent and dramatic period in its history.