Coming soon…

Coming soon…

Coming soon…

Coming soon…

Coming soon…

Coming soon…

Coming soon…

In the early-nineties, when the replica shirt industry was in its infancy and “mail order” was the closest thing to online shopping, South American club shirts were like gold dust. Even in today’s global marketplace they are are seldom found in stores, so imagine my surprise when twenty-two years ago I walked into a small sports shop in my hometown to find the 1989-90 River Plate shirt hanging on a rack beside several other Argentine shirts. My friend and fellow football enthusiast Tom bought the Boca Juniors shirt from the same period (the one with the FIAT sponsor) and I seem to recall they even had Independiente. Quite how this small-town establishment had managed to procure such an exotic selection of Buenos Aires-based club shirts remained a mystery, but rather than ask questions I quickly bought the shirt with “la banda roja” (it cost a mere £10) before someone else got hold of it.

I’d never seen a River Plate match on television, and only ever seen grainy photos of the Argentine league in World Soccer magazine, to which I was a monthly subscriber. Without internet or even satellite television, this was the only way for a twelve-year-old to stay informed of football taking place on the other side of the globe. From what the magazine pages told me, everything about Argentine football seemed different from the increasingly corporate game in Europe: the pitches were covered in ticker-tape, all the players seemed to have long hair, and they were still using the original adidas Tango balls.

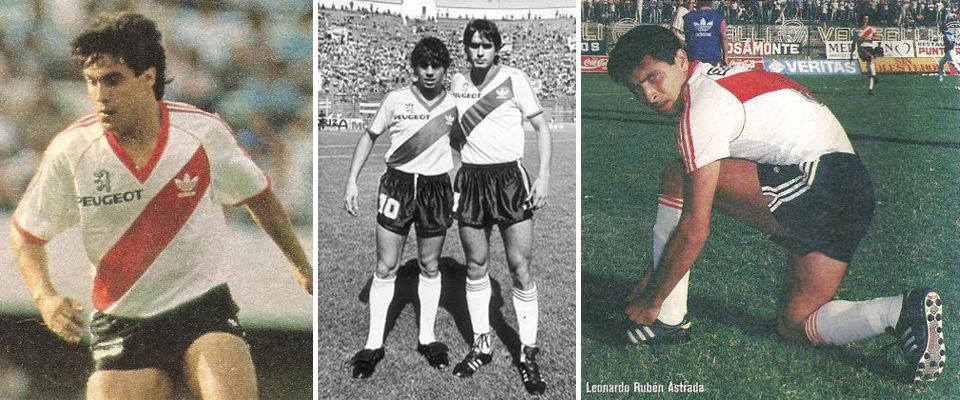

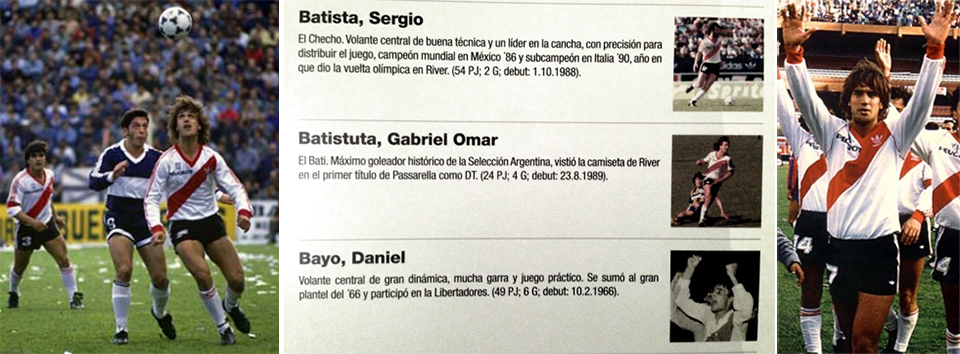

After a long barren spell River Plate had started winning again in the late-1970s, and in 1986 won the Copa Libertadores and Intercontinental Cup for the first time. But no sooner were those historic victories achieved that the team began to break up. The elegant Uruguayan playmaker Enzo Francescoli had already left for France, and fan favourite Norberto Alonso retired in 1987, leaving a gaping hole in midfield. River then suffered a mass exodus that including some of South Americas’s most talented and experienced players. Between 1988 and 1989 goalkeepers Pumpido and Goycoechea, defenders Ruggeri and Gutierrez, midfielders Gallego, Borghi, Gorosito, and forwards Caniggia, Troglio, Funes, Alzamendi and Balbo all parted ways with the club. At the same time defender Daniel Passarella — the only outfield player from Argentina’s 1978 World Cup squad still active at a high level — returned to “Los Millonarios” for one final season. Immediately following his retirement he took over the coaching of the club, his first experience of management, and led the team to an unexpected Primera División title.

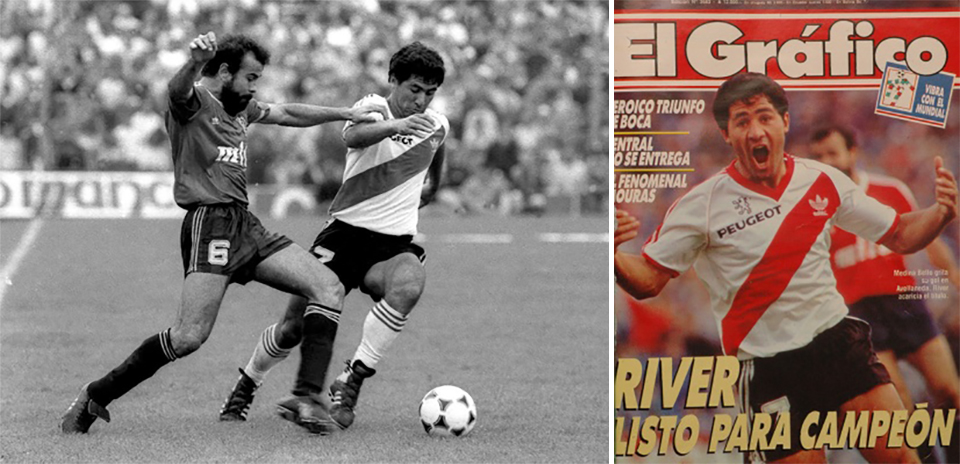

River Plate’s kit barely changed in this period, maintaining a classic adidas template throughout the 1980s. In 1989 their sponsor switched from Fate O (an Argentine tyre manufacturer) to Peugeot, and they also ditched the lion logo that had appeared on the shirt since 1984. The 1989-90 season in Argentina was the fifth and final edition to dispense with the traditional format of the Metropolitano and Nacional championships, and instead follow a standard European-style league system. The decidedly unglamourous River side kept pace with defending champions Independiente for the duration of the campaign, eventually surpassing their rivals from Avellaneda in week 27 of the season. In May, having racked up a five-point advantage, River held on for a draw in the head-to-head clash with Independiente. Two brilliant goals from striker Ramón Medina Bello in their next home match against Estudiantes were enough to secure La Banda the title with two games to spare.

Less than a month later, when the world’s national teams convened in Italy ahead of the World Cup, several of the key men in River’s title victory — including Medina Bello, Gustavo Zapata, Leonardo Astrada, Héctor Enrique, Juan José Borreli and the Uruguayan Rubén Da Silva — were missing. Carlos Bilardo’s Italia ’90 squad contained just two players from River’s championship-winning side: Sergio Batista, a midfield survivor from 1986, and defender José Serrizuela, who converted the first penalty in each of Argentina’s shoot-out victories during the tournament. There was no room either for River’s promising young forward, Gabriel Batistuta. The striker had settled quickly at El Monumental, scoring some spectacular goals in the process, only to be dropped inexplicably by Passarella midway through the season. Both parties claimed there was never any dispute between them; indeed when Passarella refused to select long-haired players for his Argentina squad in 1998, Batistuta was the one man for whom he made exception. “El Bati” left River and moved across town to bitter rivals Boca Juniors, where he forged a lethal partnership with Diego Latorre and soon caught the attention of Fiorentina.

The Primera División format became much more convoluted in 1990-91. The league portion of the competition was split into two rounds, the Apertura and Clausura, the combined points of which would determine a final league table, from which the top two would meet in a two-legged final to decide the title. River finished second in the Apertura but only tenth in the Clausura, and third overall. Their shirt was identical to the previous season, except the V-neck had become a proper collar. What I like most about this shirt is its construction. Unlike the modern kit on which River’s famous red sash is printed within the material, here it is sewn into the garment as a separate piece of fabric, lending the shirt and its most distinctive feature a little extra weight.

In 2014 I visited Buenos Aires for the first time, and one warm afternoon I took a two-hour walk up Avenida Luis Maria Campos and Avenida del Libertador, through the affluent Belgrano neighbourhood to the leafy barrio of Núñez. The purpose of this epic pilgrimage was of course the Estadio Monumental Antonio Vespucio Liberti, the home stadium of River Plate and the venue for Argentina’s historic first World Cup triumph in 1978. As I approached the stadium, I began to notice a sharp increase in pro-River and anti-Boca graffiti, while suddenly all billboards had gone from advertising cellphones and ice cream to candidates for the River Plate presidency. Avenida Lidoro J. Quinteros looks like any other residential street, but there at the end of it, like a giant Coca-Cola endorsed UFO, sits the national team’s stadium.

Fittingly for a club that likes to call itself “El Mas Grande”, El Monumental is the largest stadium in the country. Though parts of the construction look as if they’ve barely seen a lick of paint since 1978, the ground’s ultra-modern Museo River is the benchmark against which all future stadium tours must be measured. They’ve literally thought of everything: hundreds of trophies, goals on video, an alphabetical listing of every player to represent “Los Millonarios, a gallery of River-inspired artwork, plus an interactive time tunnel in which River’s successes and failures on the pitch are placed in context with important events in Argentina’s history. Alongside the vintage match-worn shirts on display is a graphic illustrating every River kit from 1901 to 2014, which is how I was able to finally pinpoint mine. Visitors are even allowed to enter the dressing room and stroll around the athletics track. Looking out into the vast arena form the comfort of the stand’s old wooden seats, as our tour guide regaled us with facts about the stadium, I took tremendous pleasure in wearing a shirt I’d bought over two decades ago, and hung onto ever since for a moment just like this. Incidentally, modern reproductions of the classic eighties shirt are now on sale at the official River Plate store for 229 pesos.

Coming soon…

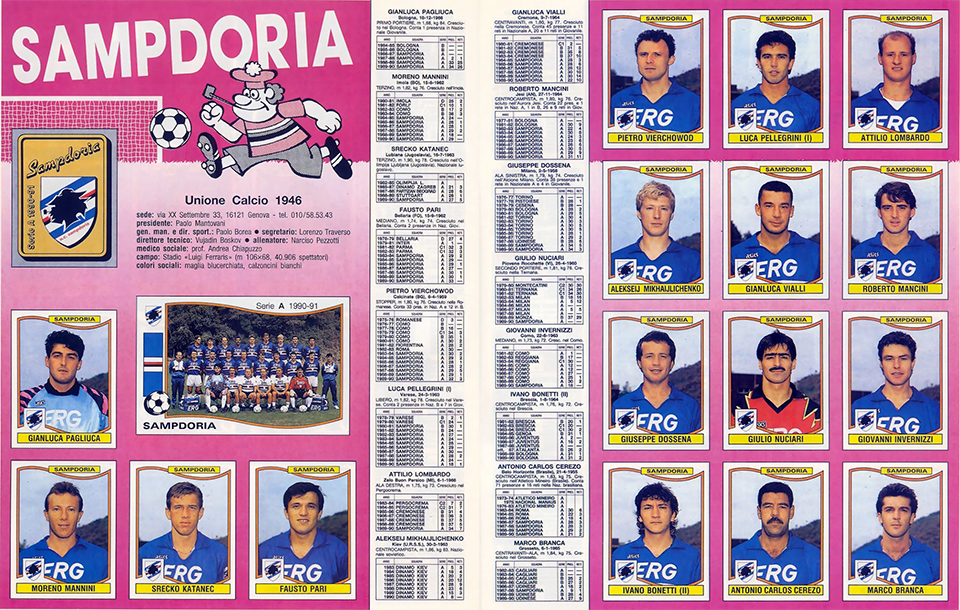

The port city of Genova is home to Serie A’s oldest and youngest clubs. Genoa Cricket and Football Club were founded in 1893; in contrast it wasn’t until August 1946 that two existing teams, Andrea Doria and Sampierdarenese, merged to form Sampdoria. The club spent its early years in the top flight without ever challenging for lo scudetto, and by the time oil trader and entrepreneur Paolo Mantovani took over the presidency in 1979 Samp had fallen to mid-table in Serie B. But in a few short seasons under Mantovani, Sampdoria were transformed into one of the top sides in Italy, and then Europe.

Perhaps the first key development in the Mantovani era was the purchase of two of Italy’s most talented forwards, Roberto Mancini and Gianluca Vialli, who arrived from Bologna and Cremonese respectively to form a formidable long-term partnership at Sampdoria. Prolific goalscorers for the club, the “gemelli del gol” or “goal twins” each scored in the second leg of the 1985 Coppa Italia final against Milan to secure Samp its first ever trophy. They were victorious in the competition twice more in the eighties, and by the end of the decade had become a force in Europe, losing the final of the Cup Winner’s Cup to Barcelona in 1989, before winning the same trophy the following year against Anderlecht.

Yet still lo scudetto eluded Sampdoria — indeed their best result in Serie A had been a fourth place finish back in 1960-61. But they had every right to dream big. Traditional title challengers Juventus were enduring a slump in their domestic dominance, and while northern giants Milan and Inter were building highly competitive sides, in recent seasons both Verona and Napoli had become first-time league winners.

Coached by the wily Serbian Vujadin Boskov, the 1990-91 Sampdoria squad was a healthy blend of domestic and foreign talent, enthusiasm and experience. Goalkeeper Gianluca Pagliuca provided a steady and spectacular presence behind rock-solid defenders Pietro Vierchowod and Moreno Mannini. In midfield Srecko Katanec and Alexei Mikhailichenko partnered with veteran Brazilian Toninho Cerezo, a survivor of the ’82 World Cup, while the glistening pate of prematurely balding winger Attilio Lombardo became a familiar sight along the flank.

In the second half of the season the Sampdoria failed to lose a single match, beating their direct rivals Juventus, Milan and Inter before finally clinching the title with a home win against already-relegated Lecce. It was a popular victory for the neutral in Italy, though some claimed Samp’s triumph was assisted by Juventus’ woeful season and Napoli’s self-combustion following the suspension of Diego Maradona. Coincidentally, Sampdoria’s city rivals Genoa enjoyed their best season in Serie A for almost fifty years, finishing fourth in the table.

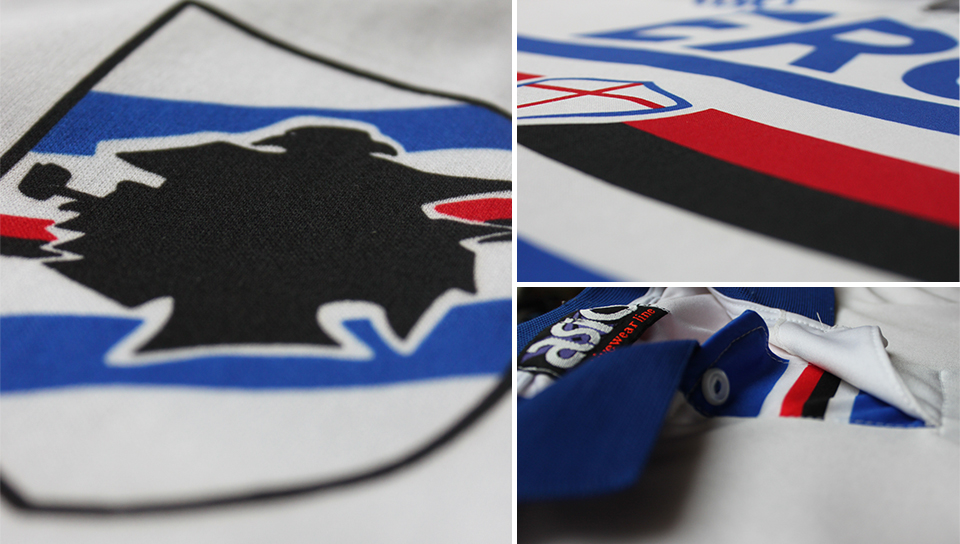

The following year Boskov’s champions failed to repeat their scudetto success, finishing a disappointing sixth. Perhaps their attention was focused on their European Cup campaign, a thrilling odyssey that took them all the way to a final against Johan Cruyff’s Barcelona at Wembley in May 1992. As was typical of the era, a tight but absorbing affair offered scant goalmouth opportunities. Nevertheless Hristo Stoichkov hit a post for the Catalans while Vialli, in his last match for the club, was unlucky not to score at least once in the second half. The contest was settled deep into extra-time by an unstoppable free-kick off the right foot of Dutch defender Ronald Koeman. Sampdoria had lost the biggest match in its history, but it was a victory that Barcelona had coveted for much longer.

Sampdoria wore white shirts that night at Wembley, identical to the one in these pictures but for the scudetto shield, missing sponsor and commemorative embroidery (not available on commercial models). The shirt was essentially a preview of their 1992-93 away strip. By now the ERG sponsor had become something of a trademark for the club, almost as much as their horizontal stripes (from which derives the nickname blucerchiati) and symbol of a pipe-wielding sailor, known locally as Baciccia. I bought this shirt in the summer of ’92 from a tiny shop in my friend’s town. The friend in question already had the long-sleeved home version of the previous season’s scudetto-winning shirt. I haven’t seen him in almost twenty years and I sometimes wonder if he still has it.

Later that summer Vialli was sold to Juventus for four billion lire. With the extra cash Mantovani brought in gifted youngsters Vladimir Jugovic and Enrico Chiesa, plus England defender Des Walker. Sampdoria already had a successful track record when it came to British imports, with Trevor Francis, Graeme Souness and Liam Brady all enjoying happy spells at the club in the mid-eighties. But Walker, frequently forced to play out of position by new coach Sven Goran-Eriksson, endured only a single wretched season in Genoa, in which the team finished seventh in Serie A. The following October president Mantovani died suddenly, leaving his son Enrico to handle the running of the club. While the Mantovani era wasn’t technically quite over, Sampdoria’s best days seemed to be behind them.

The club did its best to pull its weight in Serie A through the remainder of the nineties, but despite winning another Coppa Italia in 1994, never really challenged for the top prizes. England captain David Platt arrived from Juventus, faring much better than his international teammate Walker had in Genoa, becoming something of a local hero. But Vierchowod, Jugovic and Lombardo eventually all followed Vialli in the opposite direction to Turin. In the period that followed Sampdoria seemed to be solely a port of call for players on their way up (Chiesa, Mihajlovic, Karembeu, Seedorf, Veron, Montella) or on their way down (Gullit, Zenga, Ferri, Evani, Klinsmann, Signori). Mancini clung on to the captaincy until 1997, when he left Genoa after fifteen years, finding scudetto success again in 2000 with Lazio as a player, and later as coach of Inter and Manchester City.

Following Mancini’s departure Sampdoria were relegated in 1999 and spent the next four seasons in Serie B. They returned to the top flight in 2003 and after heroically reaching the preliminary stages of the Champions League in 2010, slipped back into the second tier the following season. This time Samp bounced back immediately, but so far their current season has been nothing if not turbulent.

Incredibly, Sampdoria’s fortunes can be tied to its famous ERG sponsor. Just as the club’s finest successes had arrived following the introduction of the petrol giant’s logo to its shirts, so its form tanked after the acronym sponsor was replaced in the mid-nineties. When Riccardo Garrone took over the club presidency in 2003, just as Sampdoria were returning from a spell in the wilderness, so the club became reacquainted with the company Garrone’s father had founded as Edoardo Raffinerie Garrone back in 1938. In January 2013 the popular Garrone died after a long illness, effectively terminating Sampdoria’s long-standing connection with the company and also briefly illustrious past.